The Deepwater Horizon oil spill changed a lot of the thinking about subsea blowouts, including how to predict the movement of the oil and gas.

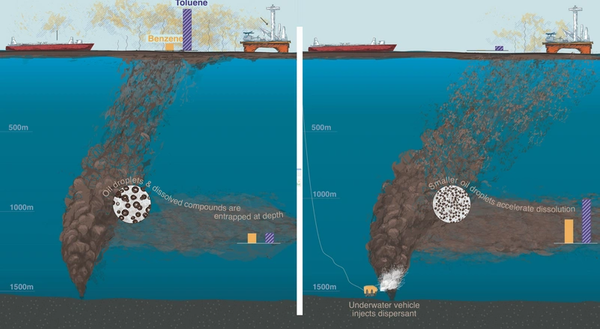

“One thing that was clear early on during the Deepwater Horizon was that dissolution of oil into water was a major process,” said Scott A. Socolofsky, Professor in the Zachry Department of Civil Engineering at Texas A&M University. Before, he added, oil had been modeled as inert, but during the Deepwater Horizon spill, “up to 27% of the mass dissolved into the water column before it reached the surface.”

Socolofsky led the development of a spill calculator that takes that dissolution of oil into the water into consideration. The Texas A&M Oil Spill Outflow Calculator (TAMOC), freely available through GitHub, is intended to help cleanup efforts for blowouts in the Gulf of Mexico, as well as preparedness planning.

Socolofsky, who has been studying bubble plumes since his PhD days at MIT in the 1990s, built the physics framework and wrote the code for the calculator; Jonas Gros, Sam Arey and Christopher Reddy built the chemistry framework; and Michel Boufadel provides data on droplet size.

The TAMOC model, originally developed for use in predicting oil spill behavior in the Gulf of Mexico, is intended to accurately predict behavior of the constituents in the spill plume from a subsea blowout, including methane, oil, seawater, and the many chemicals found in wellbores and reservoirs.

“It’s right at the source, when the spill hits the ocean, predicts what happens to it and how it gets to surface, and forecasts what is its composition is when it gets to the surface,” Socolofsky said. “To do that, we have to understand what is in the oil.”

The TAMOC framework focuses on the area close to the blowout itself, as the range of the model is tied to the behavior of the ocean currents at the spill site, he added.

The TAMOC model feeds its oil movement predictions to the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) oil spill model GNOME (General NOAA Operational Modeling Environment), which forecasts longer-term movement of the oil, such as traveling to shore.

Socolofsky is now putting the final touches on a model intended for use in Arctic spills and expected to be available this summer.

“We adapted the model for ice cover,” Socolofsky said.

What would improve accuracy for predictions, he said, is better data on droplet sizes.

“Where oil goes depends a lot on the size of the oil droplet, so that’s an important thing to predict, and it’s hard to model in the laboratory at a reduced scale,” Socolofsky said. Full-scale data is necessary, and he hopes “someone will figure out how to fund and do that in an environmentally responsible way.”