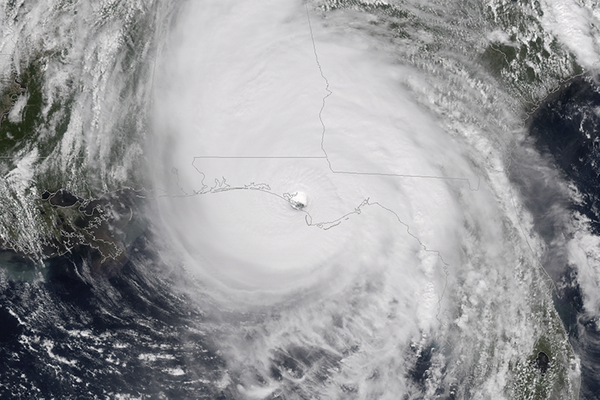

IBM’s The Weather Company has predicted a slight decrease in the 2019 Atlantic hurricane season compared to 2018, but el Niño’s delayed advance could increase this year’s storm potential.

The Atlantic hurricane season starts June 1 and runs through November 30. In early May, the Weather Company predicted 14 named storms, with the potential for seven hurricanes and three major hurricanes in 2019.

At the time, Todd Crawford, chief meteorologist for The Weather Company, expected el Niño conditions to continue throughout the North Atlantic hurricane season, which can generate an atmospheric pattern not conducive for increased tropical development. On the other hand, he said, North Atlantic Ocean temperatures are warmer than normal, which tends to produce above normal activity levels.

“The combination of El Niño conditions and warm Atlantic waters suggest a near-normal season that is similar to last year,” he said.

Last October, Category 4 Hurricane Michael prompted operators to shut in approximately 40% of the Gulf of Mexico oil output and about a third of the gas and evacuate more than 10% of the platforms, according to Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE). The month previous, Tropical Storm Gordon led operators to shut in about 10% of the Gulf’s oil and gas production and evacuate 8% of the platforms, according to BSEE.

Michael Ventrice, meteorological scientist at The Weather Company, said the organization publishes monthly hurricane season forecasts based on updated information. The early May forecast was issued under the assumption el Niño would advance.

“Now, we’re seeing some indication that el Nino may not advance as we thought it would,” he said, adding that means the forecast numbers of 14 named storms, seven hurricanes and three major hurricanes could increase. “If we are going into a state that is inconsistent with el Niño, what that suggests to me is the Caribbean Sea may be open for business, in a sense.”

El Niño conditions typically push a lot of wind across the Caribbean, which causes approaching storms to shear down and drift away, he said.

“If we’re not going to get those strong winds, there’s a concern the storms could maintain circulation,” Ventrice added.

Rob (Robbie) Berglund, energy solutions lead at The Weather Company, says oil and gas operators in the Gulf of Mexico can benefit from knowing not just the big weather picture but also hyperlocal details.

“The big picture is really cool, but unless you can get down to specifics, it’s not as useful to the asset level,” he said.

The Weather Company, which IBM acquired in 2016, uses machine learning combined with massive amounts of data to improve its forecasts.

A decade ago, Berglund said, the company could forecast and update about 100,000 different points around the world.

“It was massive, an incredible amount of data to manage,” he said. “The new platform that The Weather Company is built on forecasts 2.2 billion locations every 15 minutes.”

To deliver hyperlocal forecasts covering 500-m2 grids requires data from traditional and non-traditional sources as well as a tremendous amount of data processing power, he said. Traditional sources of weather data include FAA sensors at airports and ocean buoys. Because these are few and far between, The Weather Company is harnessing the power of non-traditional sensors, including crowdsourced contributions brought into the company with its purchase of Weather Underground, which tracks conditions wherever weather enthusiasts have placed equipment, including marinas and backyards. Airplanes can provide “a tremendous amount” of atmospheric data from flights, and the public’s mobile phones can transmit precise pressure data if the user enables that function.

“It’s evolving as we speak. We can use imaging and artificial intelligence to break that down and gain data insight out of it,” Berglund said. “We’re leaving behind the old way of doing weather and embracing the new, which is big data and artificial intelligence in weather.”