Once upon a time, many a year ago, the North Sea was seen as a new deepwater exploration frontier. Some may be surprised that it still is.

Back in the 1960s, compared with the shallow waters of the Gulf of Mexico where drillers first got their feet wet, the North Sea was seen as a deepwater province. These days, with operators drilling beyond 3,600 meters water depth, and production established in waters close to 3,000 meters deep, the water depths here are now taken more for granted. Few developments go deeper than 500 meters in the UK North Sea, with only Total’s Laggan Tormore development – a subsea tieback to shore – close to the 600 meters mark.

So, it may surprise some that the industry has been drilling in water depths well above 1,000 meters, and reaching close to 2,000 meters, for quite some time. In fact, the 10 deepest wells drilled on the UK continental shelf (UKCS) to date, according to data from the Oil & Gas Authority (OGA), are all in waters deeper than 1,185 meters (see chart).

They’re all out on the Atlantic frontier, on the Rockall Trough or in the Faroes-Shetland Trough, west of Shetland. To date, every single discovery made at these depths remains untapped. The problem is these discoveries are in environmental conditions – including the weather, the waves and currents – that are on another level to even the northern North Sea, and the subsurface has proved hard to get to grips with, both in terms of imaging it and drilling through it.

| Water depth | Region | Spud date | Operator | Prospect/discovery well | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,886 meters | Rockall Trough | May 2001 | ConocoPhillips | Dry Well (132/06-1) |

| 2 | 1,621 meters | Faroe-Shetland Trough | April 1999 | Mobil (now Total) | Tobermory (214/04-1) |

| 3 | 1,567 meters | Faroes Platform | October 2010 | Chevron | Lagavulin (217/15-1) |

| 4 | 1,556 meters | Faroe-Shetland Trough | July 2000 | ExxonMobil (now Total) | Bunnehaven (214/09-1) |

| 5 | 1,452 meters | Faroe-Shetland Trough | May 2019 | Siccar Point Energy | Lyon (2018/02-1) |

| 6 | 1,373 meters | Rockall Trough | May 1980 | BNOC | Rosemary Bank (163/06-1) |

| 7 | 1,288 meters | Faroe-Shetland Trough | March 2012 | BP | North Uist (213/25c-1) |

| 8 | 1,259 meters | Rockall Trough | April 2000 | Marathon Oil | n/a (153/05-1) |

| 9 | 1,238 meters | Rockall Trough | June 2006 | Shell (now Siccar Point) | Benbecula North (154/01-2) |

| 10 | 1,215 meters | Faroe-Shetland Trough | July 1998 | Mobil (now Total) | Eribol (213/23-1) |

| 11 | 1,185 meters | Faroe-Shetland Trough | June 2009 | Chevron (now Equinor) | Rosebank (213/27-4) |

New developments

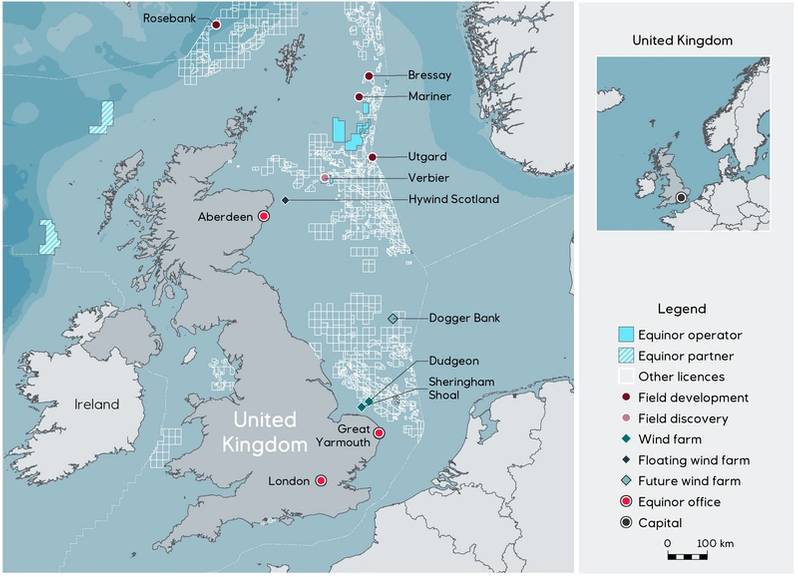

While the environmental conditions are unlikely to change, the prospects for new developments out here are. Equinor, which took over operatorship of Rosebank, the UKCS’ largest undeveloped discovery, with an estimated 300 million barrels (MMbbl), says it plans to reach a final investment decision on the field in May 2020. It’s been a long time coming – Chevron discovered Rosebank, in 1,110 meters water depth, in 2004.

There’s also been a resurgence in exploration activity in the area – above 1,000 meters water depth. Siccar Point Energy’s Cambo appraisal well, in 1,110 meters water depth, confirmed a high-quality reservoir and sustained flow. Siccar Point is now planning a phased development with the first phase targeting more than 100 MMbbl.

Earlier this year, Siccar Point Energy successfully drilled Blackrock, which sits between Cambo and Rosebank, in 1,115 meters water depth using Diamond Offshore’s Ocean Greatwhite semisubmersible. Investment research firm Edison says Blackrock could hold 200 MMbbl in reservoirs similar to Cambo and Rosebank. Then Siccar Point moved on to the Lyon prospect. As your correspondent completes this article, Siccar Point had completed drilling on Lyon, in 1,452 meters water depth (putting it in fifth place in our deepest water UKCS wells rankings), using the same rig. Results there were not so positive, with Siccar Point announcing on June 28 that the well had not encountered reservoir quality sandstone.

Many were watching Lyon closely. If successful, it could be what’s needed to create a new gas hub in the region, allowing existing smaller discoveries, including Tobermory and Bunnehaven, plus Cragganmore, to be developed, says Edison, which had estimated mean recoverable resource of 1.4 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) at Lyon – had it been a success. Andy Alexander, Chief Geophysicist and Subsurface Manager at Siccar Point, told the Devex conference in Aberdeen earlier this year, “West of Shetland is a key area for extending the basin’s future. If you look at West of Shetland and the yet to find resources, there’s 6.3 billion boe, a third of the total yet to find on the UKCS. If you include the Rockall it’s up to 50%.”

Andy Alexander, Siccar Point Energy, speaking at Devex. (Source: Devex)

Andy Alexander, Siccar Point Energy, speaking at Devex. (Source: Devex)

We’ve been here before

Exploration in the deepest waters West of Shetland isn’t that new. BNOC drilled in 1,373 meters water depth in 1980. But, some areas were under a territorial dispute for some time and that was only resolved in 1999, says Alexander. “That’s just 19 years ago, compared with more than 50 years since the rest of the North Sea was opened for exploration. Compared with the central North Sea or northern North Sea, there’s still lots of room to grow.”

Some of the technical challenges are being resolved. Brenda Wyllie, Northern North Sea and West of Shetland Area Manager, at the OGA, points out that there’s been production West of Shetland since the 1990s, such as Foinhaven and Schiehallion, in up to 500 meters water depth. Technologies to operate subsea infrastructure 100% with remotely operated underwater vehicles (ROV) has been developed and for even deeper waters, in 1,000+ meters. Drilling technologies have also evolved, as have seismic data acquisition techniques.

Subsurface, subsea and surface challenges

Still, it’s not an easy area to work in. The West of Shetland area forms part of a series of rift and volcanic passive margin basins which extend along the length of the Northwest European Atlantic Margin. This area has been hard to image due to intrusive and extrusive Tertiary volcanics, says Matt Dack, senior geoscientist, CGG Multi-Client & New Ventures.

Weather and metocean conditions also factor significantly, especially when it comes to designing surface and subsea facilities for these parts. Some of the issues for the environment Rosebank sits in were outlined by Chevron’s Peter Blake, back in 2013 (while oil prices were still high).

At that time, Chevron was working on a floating production, storage and offloading unit (FPSO) development with subsea wells, supported by gas lift and water injection, as well as dual production flowlines and chemical injection to control wax and hydrates, to tap the oil and gas condensate reservoirs at Rosebank. The design was moving toward what would have been the largest turret built for any FPSO, moored with 20 mooring lines. “It’s really pushing the envelope as far as technology is concerned,” Blake said in 2013. Part of the reason is the water depth and the number of lines coming into the turret, but also the conditions, which make riser clashing a concern.

The design wave height for the area was 108 feet, with a 140-foot survival wave weight.

In addition, there’s current shear, through the water column, in multiple directions (which the installed risers and flowlines would need to live with), and even current (1 meter per second) on the bottom. Blake said wave heights run at more than 3 meters more than 50% of the time, West of Shetland (compared with the Gulf of Mexico seeing less than 2 meters almost 90% of the time). A multi-year installation window would have also been needed in these conditions – Blake was estimating four years – where weather windows are limited.

These issues push up costs. According the Wood Mackenzie, the likes of Rosebank and Cambo come in at $40-50/bbl. “That’s pretty high,” says Kevin Swann, Research analyst, Wood Mackenzie. “Globally, for all projects sanctioned in the last three years, it’s below $35/bbl. In the North Sea some of the infill developments have been below $30/bbl. There’s a premium West of Shetland.”

Equinor’s acreage, showing Rosebank. (Source: Equinor)

Equinor’s acreage, showing Rosebank. (Source: Equinor)

Access to infrastructure

One of the big problems is gas export, says Swann. “This is something companies have been trying to look at and work out. Existing developments, Foinhaven and Schiehallion (now Quad 204) export through the West of Shetland Pipeline System (WASP), which has limited capacity. When you get things like Cambo and Rosebank, you need an export solution for the gas. You can’t flare it forever. So, it’s a challenge, how to get the gas to market.”

The OGA has an area development plan to try and address the problem and that’s for discoveries already known about, but few details were available.

Even further down the line, there’s another big challenge. Current exploration bits are focusing on the Faroes-Shetland Trough area, while pre-drill work has focused on the Rockall Trough – including £40 million ($48.6 million) of government funded seismic data acquisition and frontier focused licensing rounds. But that’s a story for another day.

Making plans for Cambo

Cambo is 125 kilometers northwest of the Shetland Islands, 30 kilometers southwest of Rosebank and 50 kilometers north of Schiehallion. Discovered in 2002, Siccar Point acquired the field license in its takeover of OMV (UK) in January 2017. Shell UK joined as a partner in May 2018.

Siccar Point has said the field has 800 MMbbl stock tank oil initially in place with an estimated recovery factor of 30-35%. The development concept will be focused on a two-phased approach with Phase 1 targeting circa 150 MMboe.

Baker Hughes, a GE company, was selected as the exclusive supplier to support the appraisal and early production phases of the project, with the ability to extend into the full field development. Installation of subsea production equipment and flexible pipes will be in partnership with Ocean Installer, for the early development phase.

Crondall Energy secured a frame agreement contract to provide support identification and evaluation of FPSO options for the development and pre-front end engineering design (FEED) technical assurance of the subsea design.

Wood Mackenzie has said it expects the field to be developed with a new leased FPSO, five subsea production wells and two injectors.