The oil majors’ retreat from frontier plays limits future drillship demand with deepwater, investment looks limited to Brazil and Guyana, writes Gregory Brown, Maritime Strategies International.

The future of offshore deepwater investment is under the microscope. In a world where oil demand may have peaked and Opec and its allies have at least 7 Mn b/d of spare capacity idled, what role does deepwater have to play in the future energy mix?

With oil prices looking unlikely to recover to >$70/b (market shocks notwithstanding) for the foreseeable future, investment prospects outside of the most prolific basins look to be challenged.

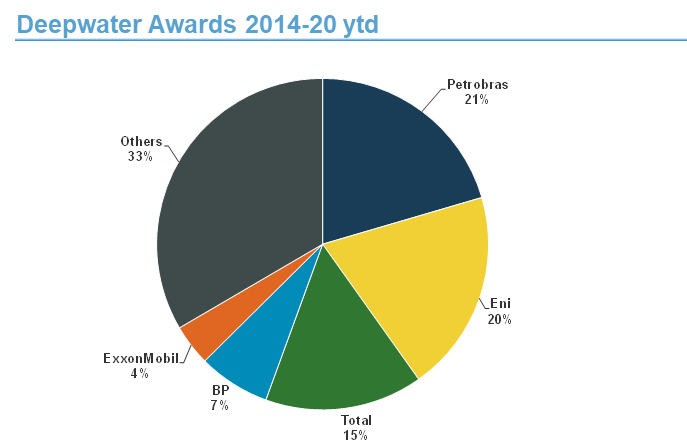

We believe that Brazilian and Guyanese projects are competitive with the vast majority of incremental production – including onshore Middle East. However, West African and Far Eastern projects are faced with structurally lower production rates and, therefore, higher costs of development.

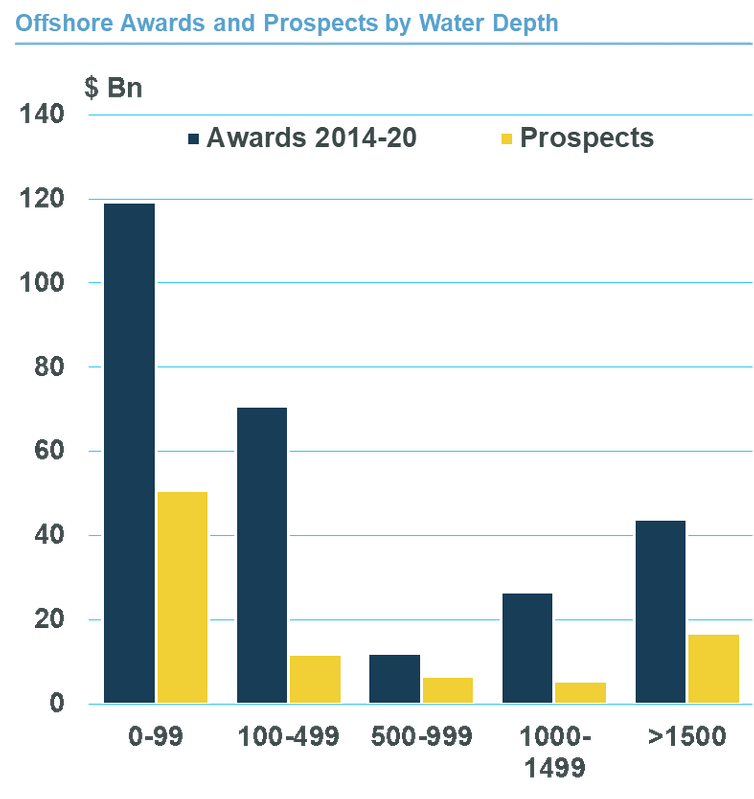

The market has only limited appetite for new production – this is reflected in the bidding pipeline amounting to just $90 Bn of opportunities versus more than $110 Bn in 2019, and more than $272 Bn of awards since 2014. What demand there is will be served by less capital intensive barrels.

Deepwater opportunities account for a dwindling proportion of the bidding pipeline – around 20% of total offshore prospects in comparison to more than 30% of awards between 2014 and 2020.

It is within this diminished market in which drillships operate. There are fewer deepwater frontier developments, and with Petrobras and Exxon looking well stacked with rigs on contract, the employment prospects for assets still in yards look anemic. Against that backdrop, securing funding to get the rigs out of the yard looks challenging.

Call off the search

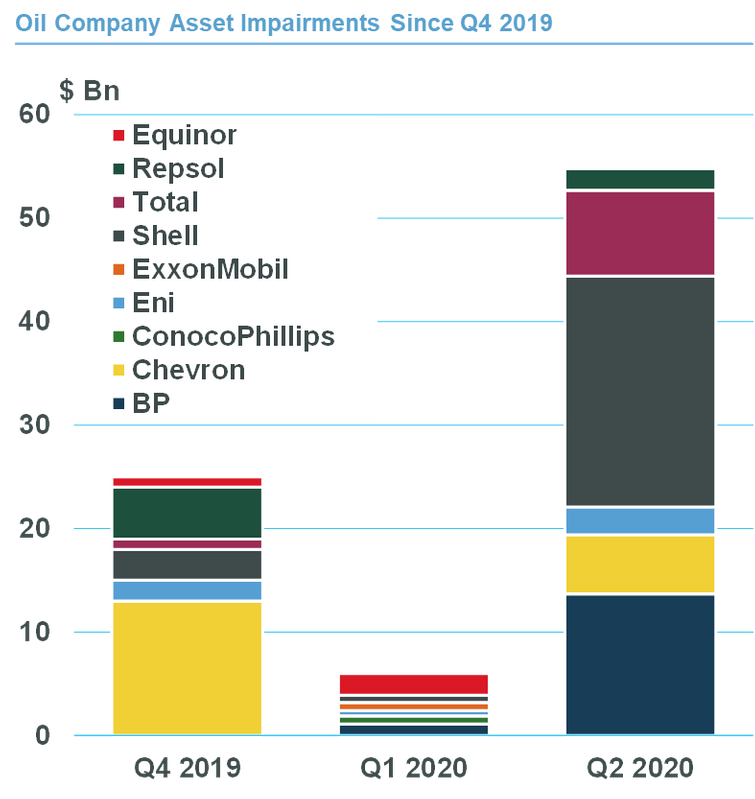

Over the first half of the year, oil companies were united in recording significant write-downs on exploration assets in the wake of March’s oil price collapse, with a number taking the opportunity to announce pathways to a lower carbon intensity future.

Those write-downs included BP’s $10.9 Bn net post tax charge, $9.2 Bn of which related to non-cash impairments across the group on lower longer-term price assumptions, the impact of weaker oil and gas prices and very weak refining margins as well as lower demand for fuels and lubricants. The impairments were announced along with a new low carbon strategy that will see the UK-based major lower production to around 1 Mn b/d – 40% lower than in 2019.

Meanwhile, Total recorded $8 Bn of impairments, Shell is taking a $15-22 Bn impairment for 2020, Eni has taken a $4 Bn write-down and Chevron took $5.6 Bn of oil and gas related charges, months after having written down its natural gas assets by $10 Bn in Q4 2019.

The impairments are substantial in size and significant in their implications. Instead of doubling down on crude production, the sector is shifting towards a portfolio weighted towards lower carbon production, alternative sources of power and a general shift in focus towards greener production.

The implicit implication is that for deepwater offshore work, demand will inevitably fall. IOCs will hold off on exploration in new markets, while new production hubs will have to be developed in the context of lower emissions targets and changing corporate focuses.

Nobody’s (de)fault but mine

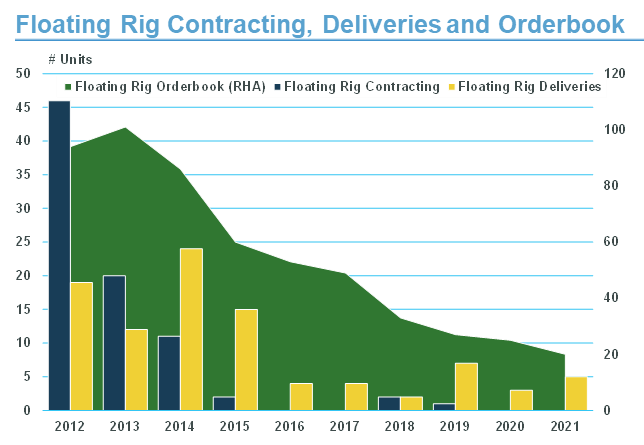

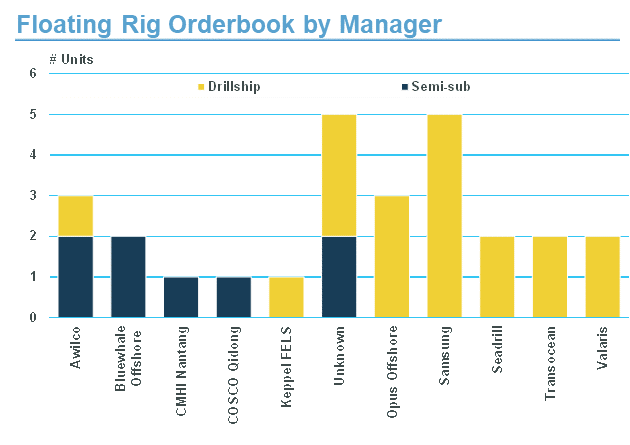

It is into this troubled market that the ~20 drillships at various stages of construction will be marketed – if they make it out of the yard. In order to do so their managers will likely have to find charter agreements, ideally with some form of prepayments or mobilization fees. Without such a charter agreement in place, securing funding to enable delivery looks particularly challenging.

It is into this troubled market that the ~20 drillships at various stages of construction will be marketed – if they make it out of the yard. In order to do so their managers will likely have to find charter agreements, ideally with some form of prepayments or mobilization fees. Without such a charter agreement in place, securing funding to enable delivery looks particularly challenging.

Of the ~20 drillships stuck in yards, many are now owned by shipyards after clients defaulted. Samsung has two drillships originally ordered by Seadrill, two ordered by Ocean Rig, and a single asset ordered by Pacific Drilling. Daewoo has the DS-13 and DS-14 rigs on its books, which are nominally owned by Valaris, as well as Seadrill’s West Aquila and West Libra assets and the Cobalt Explorer, which was originally ordered by Vantage and subsequently acquired by Northern Drilling.

We consider Transocean’s Titan drillship to be an outlier in that it is likely to be delivered. The 20 k psi rig is under construction at Jurong and has a long-term, $830 Mn contract in place with Chevron at the Anchor project located in the lower tertiary US Gulf.

The second Transocean newbuild, the Atlas, has the option to be upgraded to a 20 k psi BOP system and continues to be marketed to the likes of LLOG and Total (operators of the Shenandoah and North Platte projects, respectively) but has yet to secure a contract. Until it does, it will remain in the yard.

Every Day I Write The Book

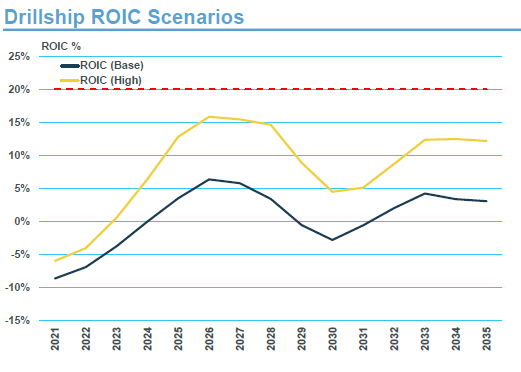

The absence of a firm contract makes an uncompleted drillship a hard sell. Under our base case scenario*, a drillship ordered in 2013 and delivered in 2021 looks unlikely to return a double-digit return on invested capital throughout at least the first 15 years of its operational life.

The absence of a firm contract makes an uncompleted drillship a hard sell. Under our base case scenario*, a drillship ordered in 2013 and delivered in 2021 looks unlikely to return a double-digit return on invested capital throughout at least the first 15 years of its operational life.

Even under our optimistic high case scenario, which assumes oil prices recover to >$70 bbl, and earnings to >$550 k/day by 2025, returns – even setting aside the >$100 Mn project costs which we exclude from this analysis) look to average just 8% through-cycle at the asset level (before corporate expenses drag the number lower)

In that environment, it is clear that drillship financials do not equate to a reasonable level of return. However, if a better entry point can be secured – i.e. at a fraction of the original build cost – we believe that returns could be ~20% using our base case earnings and utilization forecasts.

With distressed selling likely to become more commonplace as owners embark on a litany of rationalization programs, the subsequent book value write-downs would give rise to opportunistic sources of capital. The difficulty will be finding a willing investor untouched by significant prior losses. The returns on offer would likely have to be considerably higher in order to attract the marginal buyer.

* The MSI base case assumes a newbuild cost of $552 Mn (2013 figures), an LTV of 70%, the gross cost of debt of 7.33%, straight-line depreciation over 25 years, 18% tax rate, and MSI’s Q3 2020 forecasts for earnings and utilization. High case ROCE assumes MSI’s high case earnings and utilization driven by higher commodity prices. None of newbuilding project costs, owner’s spares or the 5 year SPS are included in this calculation – these are significant costs and would make the returns even worse.