While the tanker market had a strong run at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a report released this morning by BIMCO, tanker shipping will not benefit this year from the usual strong winter seasonal effect. Though the new lockdowns being introduced in many countries are less strict than in the spring, the effect on tanker shipping will be worse, given the supply glut of Q2. The news of an effective vaccine offers some hope of a global oil demand recovery but, however it comes about, it will be slow and drawn out, and it will be at least 2022 before global oil demand returns to pre-pandemic levels

The arrival of winter usually gives a seasonal boost to tanker demand and, although much has changed in 2020, many were still counting on an improvement – even a slight one – to the sector. However, the new lockdowns and travel restrictions imposed as a result of rising COVID-19 infection cases, coupled with stock drawdowns, have dashed these hopes.

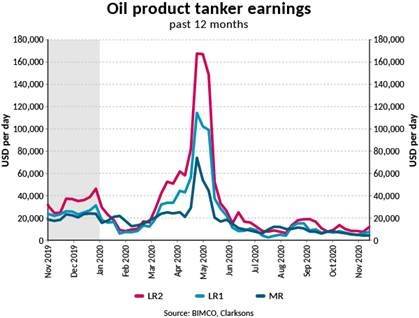

Oil product tanker earnings have certainly got the memo that the winter boost has been cancelled this year, with the high earnings of April now long gone. An average LR2 could expect to earn only $7,416 per day and an LR1 $6,147 per day in the spot market; a Handysize is looking at average earnings of $1,730 per day, after having fallen to just $411 per day in October. Bear in mind, for oil product tankers to be profitable, these daily rates must cover both operational and financing costs, which they are a long way from doing at current levels.

This is the inevitable result of the wave of low-priced cargoes in April and the massive demand impact the pandemic has had. Putting it into a longer-term perspective: monthly earnings for an MR tanker in the autumn of 2016, when the market crashed following several quarters of higher earnings, fell to ‘only’ $7,201 per day. This October, that figure stands at $6,198 per day.

Crude oil tanker earnings haven’t fared much better. At the start of November, a VLCC could expect to see average earnings of $12,806 per day in the spot market, less than half of what is needed to break even. Similarly, on 6 November, both Suezmax and Aframax earnings were considerably below break-even levels at $6,890 per day and $4,728 per day, respectively.

Lower demand for oil products, and by extension crude oil, are the natural result of rising infection levels. Lockdowns, in particular, and travel restrictions – international and domestic – directly cut into demand. But some activity is also being restricted beyond what is mandated, as rising case numbers eat into consumer confidence and a desire to travel.

The new lockdown measures in the UK have had an immediate effect on the number of cars on the roads, putting a stop to the recovery in demand for gasoline that occurred in the summer months and through to September. On 8 November, the number of cars on UK roads stood at just 57% of the same day in 2019, having been up above 100% for several days in September. The drop is still much less severe than during the spring lockdowns, as more has remained open, including schools; in mid-April the number of cars fell to just 22% of last year’s level. The numbers from the UK reflect what is happening more broadly in the region as other European countries find themselves in a lighter version of lockdown than in the spring. Demand for gasoline in the US has also fallen slightly from its summer peak but, at 8.3m bpd, it is still up 65% from its trough in April.

After an increase in the number of flights and passenger numbers over the summer, these have once again fallen. Data from the European Organization for the Safety of Air Navigation (Eurocontrol) shows that on 15 November there were just 9,697 flights in European airspace, down 62.5% from 25,864 on the same day last year. Eurocontrol expects six million fewer flights in its airspace this year compared with last. Similarly, US flight passenger numbers are down by 61.4% on last year and are once again taking a turn for the worse, after slowly rising since June.

In contrast, the number of domestic flights in China has almost recovered to pre-pandemic levels, though it is not a V-shaped recovery, as the decline significantly outpaced the recovery. The first week in October marks Golden Week in China, traditionally a time for much travel; while the rest of the world is still mostly stuck at home, 637 million people travelled in China over the course of the week. Though an impressive number, this is still down 18.5% on last year, which likely reflects lower international travel. International flights into China remain at less than half their pre-pandemic level with tight controls on who can enter the country.

China was very active in buying crude oil in the second quarter of the year to profit from the low prices. Over the first 10 months of the year, Chinese crude oil imports rose by 10.6%, reaching 458.6m tonnes. They slowed in the last months though, peaking at 53.2m tonnes in June and falling to 42.6m tonnes in October. Russia has overtaken Saudi Arabia as the largest source of Chinese crude oil imports. Imports have totalled 64.6m tonnes so far this year, compared with 63.6m tonnes in 2019. This has lowered demand for tanker shipping, as a considerable share of imports from Russia are delivered by pipeline or rail.

On the other hand, there has been a 110.8% increase in imports from the US in the first nine months of the year, with the third quarter showing particularly strong growth. This is put down to the Phase One trade agreement between China and the US apparently boosting volumes, despite the final target still being far out of reach. Compared with the larger crude oil exporters to China, the US share remains relatively small; imports from here totalled 10.9m tonnes in the first nine months of the year.

Refinery throughput in China has continued to show strength, with October posting a new record of 59.8 million tonnes, up from the previous high in July (59.6m tonnes). So far this year refinery throughput in China has averaged 55.5 million tonnes, still up from last year (+2.7%), but if the trend holds for the full year, it is a considerable slowdown in growth from the +7.8% in 2019 and +6.2% in 2018 (source: National Bureau Statistics China).

Contrastingly, Chinese oil product exports have fallen considerably. Accumulated Chinese oil product exports are down 5.4% after the first nine months of the year, after having been up by 3.8% in the first half of the year. Exports in September were less than half of the 8 million tonnes record set in April.

It was inevitable that Chinese oil product exports would be hit. Oil demand in the rest of the world is still considerably below its pre-pandemic levels and, as global stocks are high, drawing on these has been prioritised above new imports.

US imports of oil products fell 17.7% in the first eight months of the year (exports down 11.2%) and imports by OECD countries of gasoline, middle distillates and residual fuel oil are down by 19.3%, 15.6% and 11.8%, respectively.

Product tanker fleet is set to grow by 2.5% this year, down from the 4.7% of last year (ordering ahead of IMO2020). Deliveries of oil product tankers have been low too, with owners hungry for new tonnage to beat the IMO 2020 Sulphur Cap and the boost many thought it would bring to oil product tanker shipping.

Some 4.7m DWT have been delivered so far this year, putting the product tanker market on track for the lowest deliveries since 2002.

Net fleet growth is not experiencing such multi-year lows though, as demolition activity of just 1m DWT means the fleet will grow by 2.5%, down from the 4.7% last year, but higher than the 1.8% in 2018.

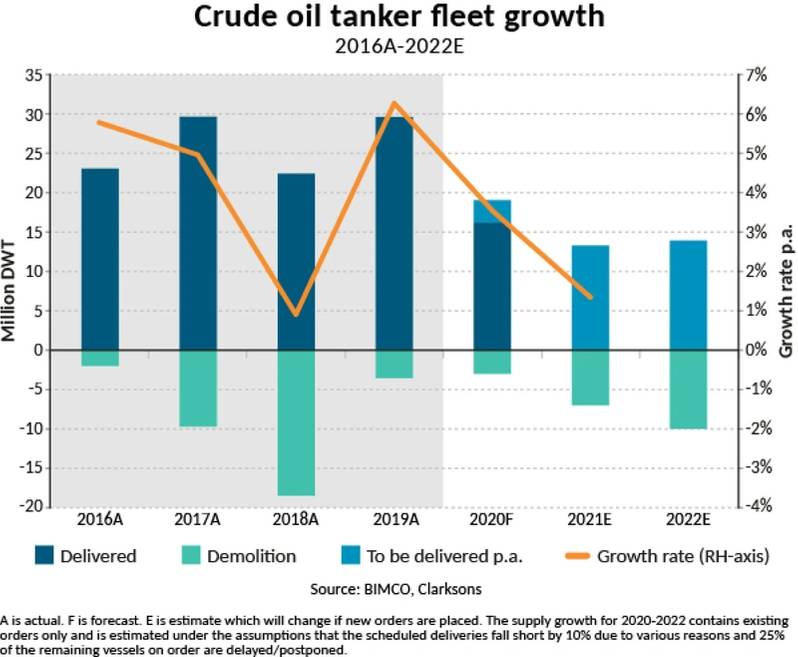

Deliveries of crude oil tankers have also fallen from the highs of the past few years, but one only has to go back to 2015 to find figures at a lower level. So far, 16.2m DWT have been delivered, against demolitions of 1.1m DWT, leaving year-to-date fleet growth at 3.1%. Full year fleet growth is expected to be 3.5%.

Of the crude oil tankers, VLCCs have seen the highest fleet growth this past year. An average size of 304,371 DWT means that the 32 VLCCs delivered have added 9.7m DWT to the market. At the other end, there have been no VLCCs demolished since June 2019, leaving the fleet growth unchecked.

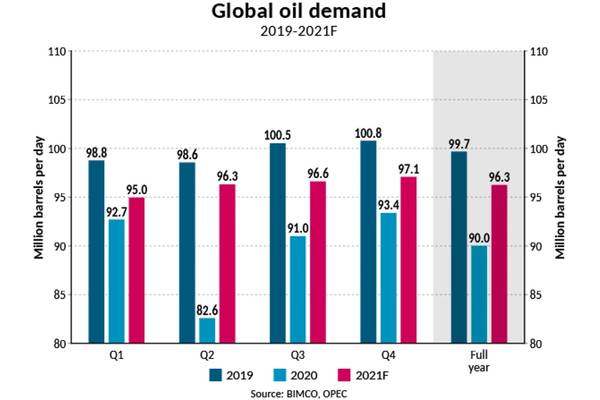

Tanker shipping will enter next year facing many challenges. The first, and most obvious, originates from lower global demand. Though it will rise from 2020, oil demand will remain below 2019’s levels and, as it looks now, considerably below. In its November report, OPEC forecasts that global oil demand in 2021 will rise from the 90m bpd this year to 96.3m bpd. It believes demand will remain depressed until at least the middle of the year. The 6.3m bpd increase is strong growth by any standard, but not enough to bring it back up to the 2019 level of 99.7m bpd.

Even if an effective vaccine can be rolled out by the summer of 2021, a sudden bounce back in oil demand is not expected, as transport and industrial fuel demand will remain lower. Eurocontrol forecasts that it will take until 2024 for flight numbers in Europe to return to pre-pandemic levels. It also warns that if a vaccine proves ineffective, a return to 2019 levels will take 10 years.

Another challenge facing tanker shipping is the drawdown of stocks. Stocks have been high since the second quarter of the year, when the huge oversupply of oil, as a result of the price war, meant supply far outpaced demand. Since then, supply has been better matched to demand, with stocks slowly being drawn down. This causes two problems for tanker shipping. Most notably, stocks are often already to be found in the consuming region, meaning the oil has already been shipped to where it needs to be. The consequence being that for as long as stocks are being drawn upon, demand for shipping will be lower than if the goods were being imported.

Stock draws also mean tankers that have been engaged in floating storage since Q2 are now being freed up and returned to the market, adding to the woes of overcapacity.

In the longer term, the low oil price and refinery margins look as though they are here to stay for a considerable period, with the fine balancing of matching changing demand and supply to be navigated. Lower demand and refinery margins have already forced many refineries to shut down permanently, with more looking likely to follow.

The low oil price is affecting crude oil production both now and will do in the future, as some producers need a higher price to break even than others. A typical comparison would be between the US and Saudi Arabia, the former faces much higher production costs than the latter. The upshot is that the US, whose share of global crude oil production has been steadily rising as a result of fracking, could start to see its share fall. This would be bad news for the tanker shipping industry given the much longer sailing distances from the US to the Far East than from the Middle East.

Finally, tanker shipping has faced much volatility over the past year as a result of geopolitics – ad hoc sanctions on certain tankers, oil price wars, and so on – all of which creates a lot of uncertainty, but also opportunity with freight rates sent soaring on several occasions.

With a new US president set to take over the White House in January, tanker shipping may find itself breathing a sigh of relief as geopolitics become less fraught. However, many in the industry who face a challenging 2021 may find themselves longing for the short-term boosts the chaos of the Trump era brought to the freight market.