Dr. Anil Sharma is a wealth of knowledge on ship scrapping, having started GMS 25 years ago, getting into the business of buying and disposing of old U.S. MarAd and Russian navy ships as a sideline while teaching as a college professor in Maryland. Today his company is dominant in the field, and in the last year he has seen an unprecedented 70% run up on ship scrap prices, approaching $500 per ton. He weighs in on ship scrapping trends and direction.

By Dr. Anil Sharma’s estimation, GMS is the world’s dominant player in the business of buying ships and offshore assets for recycling, by number of ships, about one-third of the world’s annual transactions; rising to 40% if measured by lightweight tons. “We tend to do big ships, big projects,” said Dr. Sharma. “In terms of annual number of deals, the highest we have done is 300 plus ships in one year … about one ship a day, and our lowest is around 150 ships. So (for GMS) it moves between 150 to 250 (ships per year) depending on how bad the world economy is, depending on which sector is being punished.”

The ship disposal business, like maritime itself, is highly cyclical. Today in maritime, both the container shipping and the dry bulk sectors are enjoying strong years, so ship scrapping activity in those two categories will be little to none. Conversely, the tanker, the cruise and the offshore sectors are all being ‘punished’ and ship scrapping activity is picking up speed, particularly in the offshore sector.

There are many factors that determine the life cycle of a ship, and while life-cycles can vary greatly by sector, conventional wisdom suggests 20 to 25 years of service yields a fairly good return on investment. But life cycles change, and today commercial pressures in certain sectors, combined with fast-evolving environmental and emission reduction pressures, are conspiring to cut the life of ships in some sectors shorter – in some cases like the offshore market, dramatically so.

“Everything has a life cycle and that life cycle changes,” said Dr. Sharma. “For example, cruise ships tend to have the longest life cycles, but when COVID hit, a lot of cruise ships were recycled. Otherwise, the shortest life cycle I'm seeing right now is in the offshore space, where we are seeing vessels 10 years old and even younger units being recycled. It is insane.”

“In terms of the commercial aspect, it just took off. we gained in prices about 70% increase in residual values and scrap values in a matter of about eight to nine months: that's huge, a 70% increase is unprecedented,” said Dr. Sharma. “Somebody was asking me just today, where is this going to stop? Because every day it's a new benchmark, and prices keep on going higher.”

“In terms of the commercial aspect, it just took off. we gained in prices about 70% increase in residual values and scrap values in a matter of about eight to nine months: that's huge, a 70% increase is unprecedented,” said Dr. Sharma. “Somebody was asking me just today, where is this going to stop? Because every day it's a new benchmark, and prices keep on going higher.”

The Offshore Conundrum

Looking at the beleaguered offshore sector, Dr. Sharma said in the past he could count the number of offshore assets being scrapped on the fingers of one hand, “or maybe less than ten.” But today “the floodgates have now opened and the numbers are large.” But there are challenges.

The challenges in the offshore oil and gas industry today are well-recorded, and now you can add to the list the financials behind the decision to scrap or keep, as Dr. Sharma said that generally a ship owner would estimate a residual value of 20% remaining on a vessel after 20 to 25 years of service. “Twenty to 25 years is a long time to amortize 80% (of the purchase cost),’ but that doesn't happen in offshore today. The gap between the new build price and the residual value is enormous,” he said. For the larger ships with the higher daily cost, the decision to scrap was not difficult.

But in the Jack-Up market, for example, owners were at a standstill for nine months or more, worried that if they scrapped and their competitors did not, they would risk missing an opportunity, such as the steadily rising price of oil, which today sits just north of $60 per barrel. “My point is: offshore is a huge unit. This is a where modern ships are being recycled. And when they do recycle, very rarely is it one unit, they sell fleets.”

Dr. Sharma sees "offshore" with FPSO, semi-subs, drillships, Jack-Ups and other units, as a big sector when it comes to recycling, while the other related sector that is emerging this year is going to be tankers. He said that the reason for this was because for a long time, "the crude business has not recycled," and now with the value and charter rates coming down, with the contango pretty much disappearing, meaning demand for tankers to serve as storage units dropping.

The COVID Impact

When COVID started impacting the world economy in March and April 2020, Dr. Sharma said that the ship scrapping business reacted much like the rest of the world: a complete standstill. “This is a black Swan event, totally unprecedented,” said Dr. Sharma. “When this started, we couldn’t see the bottom. For the first time (ever) we stopped quoting prices. I didn’t know how to quote because there was no demand.”

The recycling yards – the world – were in lockdown, and GMS’ business model of taking about 50% of its ships ‘as is, where is’ proved particularly problematic with the difficulty in air travel globally. “We are constantly having crews fly all over the world, and that became a nightmare because of COVID and canceled flights,” said Dr. Sharma. “We were chartering planes, so the costs were going up, and even when we could land, you'd be quarantined for 14 days in hotels. Logistically it was one of the most difficult years, and the crew part has not really gone away.”

But while the logistics difficulties mounted, something odd happened. Ship scrapping prices took off.

“In terms of the commercial aspect, it just took off. we gained in prices about 70% increase in residual values and scrap values in a matter of about eight to nine months: that's huge, a 70% increase is unprecedented,” said Dr. Sharma. “Somebody was asking me just today, where is this going to stop? Because every day it's a new benchmark, and prices keep on going higher.”

Looking Ahead

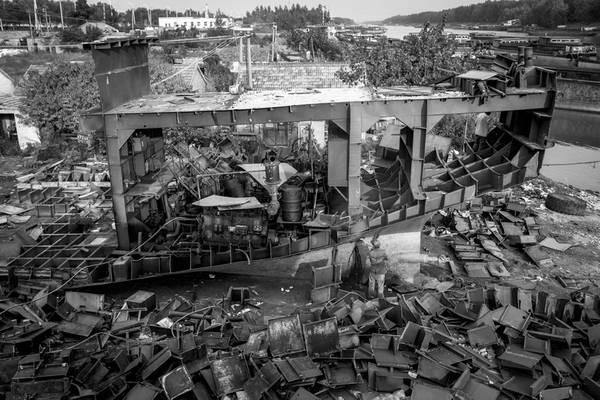

There are many moving parts in the ship scrapping business, a recycling industry that has historically had an image problem with visions of beached ships, pollution and a dearth of worker safety. Dr. Sharma contends the spotlight is somewhat unfair, and driven by the Hong Kong convention the industry as a whole has improved its practices over the last decade. “I think most of us have accepted Hong Kong convention as the main way for sustainable recycling,” said Dr. Sharma. “So from the regulatory perspective, I think things are getting in place in terms of what convention to follow, what defines sustainable recycling. And people are accepting that there are good yards and bad yards everywhere. It is not country specific it is yard specific.”

In terms of future pricing, Dr. Sharma can rely on nearly three decades of insight and experience, but at the end of the day there are myriad factors beyond anyone’s control that dictate ship scrap prices.

“(Recently) a bank was saying that the RV they're looking two years forward is only $50 per ton. Keep in mind today that it is almost $500 per ton,” said Dr. Sharma. “So people are like, really? Personally, I don't see it that low. I normally tell my team a price around $300 per ton is a relatively good price to hedge forward risk. And we go case-by-case, because these cycles are very fast. You don't have those nice gentle cycles because we are in the commodity business.”

In the wake of 2012, which was the biggest year in ship recycling premised on the massive fleet build up through 2005 just prior to the global economic crash, Dr. Sharma said “everyone wizened up, and net fleet growth was quite sensible.” Instead Dr. Sharma likens the future of ship scrapping to ‘kangaroo hops’: a surge of business from one sector, then nothing. Then another surge. “It makes our life more interesting.”