The Caspian region – home to 6 million barrels of oil equivalent per day of liquids and gas production – has been near the forefront of the global energy sector since the 19th century. It is core to most of the majors and has a resource base that should be primed for longevity.

But the landlocked region risks facing an upstream investment crisis in the 2020s. This could shape the strength of hydrocarbon-dependent economies like Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan for decades to come.

So, what’s created an investment cliff-edge, and can it be avoided with new reforms?

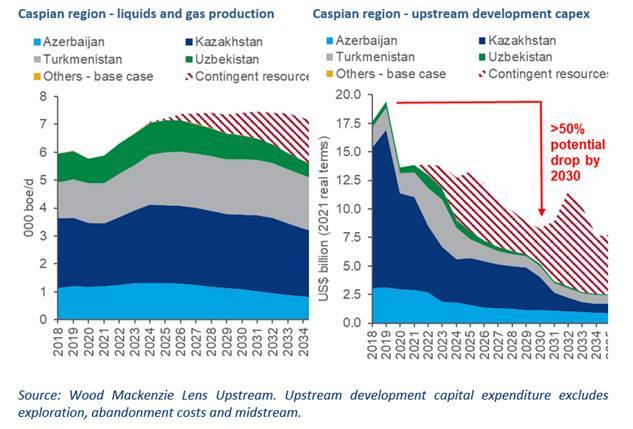

In our base-case view, marketed oil and gas production in the Caspian region will grow in the 2020s. This is largely because of phases that are commissioned or under execution at the dominant megaprojects. However, 2030 upstream development capital expenditure looks set to be less than half its 2019 level of almost US$20 billion (in 2021 terms).

These figures exclude upside from new exploration success. Prospective volumes remain high thanks to the quality of the subsurface. But the largest such opportunities face their own obstacles to commercialization. This includes BP and SOCAR’s new, potentially giant, Shafag Asiman deepwater gas find in Azerbaijan.

The region’s upstream investment mix mirrors its top-heavy production profile. The majority of spend is at the five majors led megaprojects in Kazakhstan (Kashagan, Karachaganak and Tengizchevroil) and Azerbaijan (ACG and Shah Deniz).

We see three key factors contributing to the looming cliff edge:

The megaphase era is ending

Unlike between 2000 and 2020, there is no “elephant-sized” brownfield development FID imminent. Kazakhstan’s US$45 billion Tengizchevroil expansion (FGP-WPMP) is winding down annual investment from its peak in 2018-19.

The Chevron-led megaphase is the most recent to sustain regional capital expenditure. It could be the last, as the majors target quite different future portfolios and even more robust project returns.

FID-ready greenfield options are lacking

Caspian upstream investment suffers from a chronic lack of diversity. Brand-new major capital projects that are ripe for evaluation are few and far between.

The region does not lack for discovered undeveloped resources. But, when it comes to new larger-scale greenfield projects, especially gas, the commercial case is often far from compelling.

Upstream growth projects require the majors, but may struggle to attract them

The region’s upstream sector needs highly experienced IOCs because of the complexity of its largest prizes. But those companies are managing their future upstream investment more tightly than ever before. For the majors in the region:

• Base megaproject operations largely remain close to the core of the core.

• Large-scale discretionary investment options struggle to meet key commercial hurdles. Without significant optimization, breakeven prices are typically too high and payback periods too long.

So what needs to change?

Lower costs – doing projects differently

Too many major capital projects of the past have suffered cost blowouts and delays. New investment must be nimbler, weaken the region’s cost premium and enable early monetization from shorter capital cycles.

Pre-tax economics are a fundamental challenge. Most of the largest pre-FID projects – brownfield and greenfield – do not generate a before-tax IRR above 20%. For greenfield developments, basic synergies must finally come to the fore.

Higher investor share – governments focusing on economic multipliers

There is no easy solution. In Kazakhstan, our bespoke analysis of a large model offshore oil field shows that no single tax or regulatory lever can bring a project to commercial competitiveness and a 15%+ post-tax IRR. This would take a complex combination of fiscal incentives and operator-led project optimizations.

This is not to say that governments should attract investment for its own sake. Instead, it recognizes the economic multiplier effects that large-scale projects bring. Especially if local content is high.

Lower carbon – linking decarbonization and upstream priorities

Regional governments increasingly share the net-zero ambitions of their largest international investors. New large-scale projects must fit the bill.

For the majors, regional decarbonization is a portfolio play too. Several have already taken wind and solar positions, benefitting from their lengthy regional experience.

A pressing challenge is to bring together the two sides of the investment picture – upstream and carbon-neutral. In our view, host governments should proactively create fiscal incentives to support both streams of investment.

Gas monetization – unblocking options to unlock value

The region’s vast gas resources should be a blessing amid the energy transition, from deepwater Azerbaijan to Central Asia’s prolific basins. But, even as exports rise and exploration shifts towards gas, upstream economics largely remain liquids-driven.

There are clear competitive challenges for uncontracted Caspian gas in core export destinations – the EU for Azerbaijan and China for Central Asia. Furthermore, governments are too accustomed to cheap gas at home.

Domestic reforms are needed. This would boost the rationale for optimizing upstream development concepts, substituting major capital projects with incremental tie-backs to existing infrastructure.

Regional cooperation – reducing the reliance on Majors

Given the technical and financial obstacles at the Caspian’s largest projects, regional NOCs are not yet equipped to take greater operating responsibility. But recent progress between Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan for the long-disputed offshore Dostlug field shows how cross-border partnerships could spread the capital load and foster collaboration.

Kazakhstan’s Kashagan oil giant will be a regional bellwether

Thoughts about the Caspian’s upstream competitiveness often lead to Kashagan, and for good reason. Its long-term development plan must resolve multiple commercial and technical conundrums.

There are immediate milestones to ponder, not least the need for Kashagan’s updated full-field development concept to receive official approval later in 2021. This will enable studies to continue on a mix of pre-FID phases to boost oil production capacity.

Work over the next few years will truly test the majors’ appetites for another long-lead investment project in the Caspian region. If Kashagan expansion is to be realized, it will be thanks to successfully addressing the challenges.