Australia's vast liquefied natural gas (LNG) sector is betting its future on carbon capture and storage (CCS), a technology it says is vital to decarbonization and is proven.

Convincing everybody else is going to be the tricky part, especially since the only large-scale project of its kind so far hasn't exactly been a resounding success.

Decarbonization and reaching net-zero emissions by 2050 was the major theme of this year's gathering of the companies that make Australia the world's largest LNG exporter at the Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association conference this week.

CCS has a poor public image, largely because it is viewed as failing to deliver on its promise, and is an expensive solution to a problem that environmental and renewable energy proponents believe is better solved by eliminating the use of fossil fuels.

Much of the perceived failure stems from the inability of CCS to remove carbon when fossil fuels are burnt, especially in the case of coal-fired electricity generation.

For several years the coal mining industry and lobby touted CCS as a solution that would allow them to operate over the long term.

That promise was never delivered upon. It would be extremely challenging to find a serious energy industry player or analyst who sees any future in CCS for coal-fired power plants.

But Australia's LNG industry, which vies with Qatar and increasingly the United States as the world's biggest exporter, sees CCS as a viable path to decarbonization in its upstream sector.

The plan is both simple and vast in its scope.

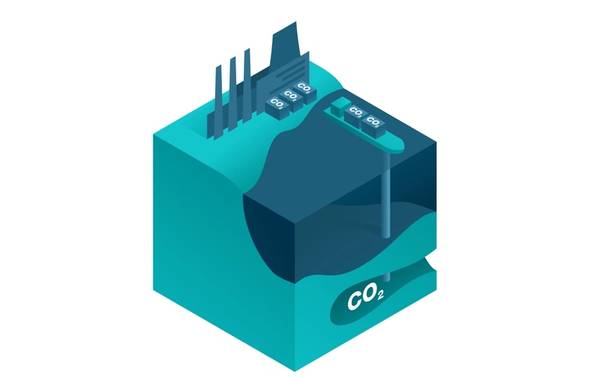

LNG producers would dramatically lower their Scope 1 and 2 emissions by capturing the carbon emissions produced in the extraction and liquefaction processes and injecting them back into depleted natural gas and oil reservoirs.

The industry proponents of using CCS repeatedly refer to the process as "proven technology" that is ready to deploy at a large enough scale to make a difference to global emissions.

While it is true that there are several CCS projects at upstream oil and gas ventures, it's gilding the lily to say this is a technology that's ready to be deployed on a massive scale at a price that makes economic sense.

Much is made of the world's largest CCS project at the Chevron CVX.N operated Gorgon LNG plant in Western Australia.

This project aims to capture and store 4 million tonnes of carbon emissions each year, but it only operated at just slightly better than half of that in 2021, storing some 2.1 million tonnes.

It is to Chevron's credit that in an industry that has had a reputation for being tight-lipped about problems, the company has acknowledged the issues with Gorgon, effectively saying it's on a steep learning curve and aims to reach its targets.

CCS INFANCY

The point with Chevron's struggles at Gorgon isn't to prove that CCS at upstream oil and gas projects is unviable, it's that there are technical challenges that make it difficult, and the technology is still in its infancy when it comes to deploying on a significant scale.

Another large-scale CCS project in Australia is being undertaken by the country's second-biggest oil and gas producer Santos, which is building a 1.7 million tonne a year CCS facility at Moomba, a gas hub in the country's remote center.

Santos Chief Executive Kevin Gallagher told the APPEA event that under the International Energy Agency's net-zero pathway CCS will have to store about 7.6 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide each year, a staggering 200 times what is currently being achieved.

That neatly sets out the scale of the challenge, but it also raises the question as to the cost of achieving this goal.

Effectively, the LNG industry will need to be able to generate carbon credits to justify CCS investments.

This could be viewed either as a sensible way to allow fossil fuels to continue existing in a carbon-constrained world, or as just another handout from taxpayers to the fossil fuel industry.

But perhaps the main challenge for Australia's LNG producers is overcoming the hurdle of public skepticism over CCS, both its cost and its effectiveness.

To do so, the industry will have to demonstrate that the technology can be deployed at scale and speed, without fleecing the taxpayer, and can make a genuine contribution to net-zero goals.

For Australia's LNG industry, putting CCS front and center of their social licence to operate is a massive risk, but it would also appear that making it work is largely within their own hands.

(Reuters - Reporting by Clyde Russell - Editing by Christian Schmollinger)

The opinions expressed here are those of the author, a columnist for Reuters.