Houston-based Nauticus Robotics’ first production Aquanauts and Hydronauts will head into the wild and closer to full commercialization this year, with testing planned in Norway and in the Gulf of Mexico. Founder and CEO Nicolaus Radford discusses the past few busy years for the tech start-up.

It’s been a relatively fast journey for Nauticus. Set up in 2014 (as Houston Mechatronics Inc), the company has been a bit of an outsider in the offshore industry, against incumbents offering (for the most part) more traditional looking underwater robotic systems.

However, the third quarter of 2022 saw the company (whose investors include Schlumberger (SLB) and Transocean) complete a business combination with CleanTech Acquisition Corp., netting it nearly $60 million to fund its first fleet of ocean robots; list on the Nasdaq exchange; agree a trial with energy giant Shell; win a contract with the U.S. Defense Innovation Unit; and agree a defense related partnership with tech giant Leidos.

It now has three of its second-generation Aquanauts in build in Vancouver, which will be used on trials in the Gulf of Mexico and offshore Norway, and two Hydronaut uncrewed surface vessels (USVs), which will act as launch and recovery systems and surface gateways to Aquanauts, in-build in the UK.

CEO Nicolaus (Nic) Radford, who set up the firm in his living room eight years ago, doesn’t hold back his ambition. Innovation has been “mind numbingly slow” in the offshore industry, he says. Part of Nauticus’ ambition is to “put an adrenaline shot” into it, by taking robotics technology developed for space flight into the ocean.

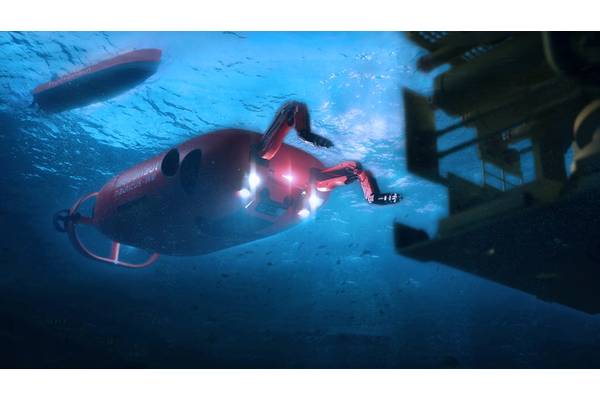

“My dream is to have a network of Aquanauts and Hydronauts out there working, a whole Navy of them, being controlled by control centers around the world, out there 24/7 doing their thing. That's the core of the business. There's an ocean of opportunity to take advantage of,” he says, from fisheries to countering global security threats, which have heightened recently, with increased underwater surveillance to protect critical infrastructure, such as pipelines and communications cables. Image courtesy Nauticus

Image courtesy Nauticus

“I'm fired up as you can as you can possibly get about this industry and I think there's so many different facets to move into,” he says. “Frankly, it's huge. It's enormous, it's completely front and center right now. It's the epicenter for all of our resources, right? Food, minerals, energy.”

That adds up to an estimated $2.5 trillion marine economy, of which some $30 million could be addressable the types of ocean robotics it’s building, according to Nauticus.

Born in Illinois, Radford graduated with a Bachelor of Science in electrical and computer engineering then joined NASA’s Johnson Space Centre and pretty much went straight into robotics, including DARPA sponsored programs, before moving to Houston, working with United Space Alliance and then Oceaneering Space Systems as a contractor to NASA, again in robotics.

“At NASA I learned a ton of stuff, but uncovered this idea that there was meaningful change to be made in the ocean domain,” he says. “I had had some exposure to the ocean world before and remember the first time I saw an ROV I was like, OK, that's cute, but we can do so much better. Then you realize they don't want to do any better.”

A part of the problem is incentives and the ability to disrupt. “Some of the big incumbent players have very successful businesses, but it ties them to certain incentive structures,” he says. “When you're paid by the hour, you do not want fewer hours. So, Schlumberger (who he’d worked with at NASA) sort of challenged me, what would you do about this? I said we need to create a hybrid vehicle. We need to be able to have an AUV turn into an ROV, because we actually don't need an umbilical. It was a flash in the pan idea, and so you know we garnered some investment.”

Radford had also been working with Transocean on some drilling software and they were interested in the idea too; so they had their first investors. Since then, US government contracts, from the Navy, especially, have been a strong driver. It’s meant that, over the past four years, Nauticus has developed and tested a significant amount of technology – most of which they’ve not been able to publicize, says Radford.

“My proudest moment was when we did a fully autonomous demonstration and I was taken to the side by our customer and they basically said ‘that was the most advanced stuff they’d ever seen’. We essentially had an autonomous mission that occurred over about 20 minutes of action where the robot was able to pick up a tool, assess it, figure out a way to operate it, figure out a way where that tool could be operated on. We just put the robot in the water, we hit the on switch and sat watching with cups of coffee and it worked. We were almost crying! It was incredible.” That was two years ago in a test tank environment – they’ve not been able to share the video, he says.

Since then, testing has been in the real-world, including Lake Travis in Austin, but also coastal areas. “We have some milestones coming up which will stress that (capability proven two years ago) probably by a factor of 10,” says Radford. The Aquanauts are also getting closer to commercial work. Three (second generation) production Aquanauts are in build at International Submarine Engineering in Vancouver. A couple of them are due to head to the Tau Autonomy Center in Norway to qualify “certain actions” for a couple customers. One will be doing some pilot work in the Gulf of Mexico in mid-2023.

“My dream is to have a network of Aquanauts and Hydronauts out there working, a whole Navy of them, being controlled by control centers around the world, out there 24/7 doing their thing. That's the core of the business. There's an ocean of opportunity Nicolaus Radford, founder and CEO, Nauticus Robotics. Image courtesy Nauticus

“My dream is to have a network of Aquanauts and Hydronauts out there working, a whole Navy of them, being controlled by control centers around the world, out there 24/7 doing their thing. That's the core of the business. There's an ocean of opportunity Nicolaus Radford, founder and CEO, Nauticus Robotics. Image courtesy Nauticus

They’ll go out with a lot of autonomous capability under their belts, says Radford. “That work (with the US Navy) has meant being able to build up thousands of kilometers and hours of dive time on their autonomy software,” says Radford. It’s also meant building a commercial and defense variants of Aquanaut. “Those two platforms are in the water every single day, diving, collecting data, building out behaviors, to deploy to the production systems, so we don't have to wait till they come up the assembly line to build out their usable action. It’s a library we've been building for years now.”

The offshore pilot with Shell, planned for mid-2023, will focus specifically on testing Aquanaut’s ability to deploy a robotic tool, for carrying out inspections on pipelines. Currently, this tool can only otherwise be placed with an ROV, for which a fully crewed ROV vessel is needed, which “would be overkill” for the work it’s doing. Part of the qualification work for this tool deployment includes supervised autonomy and tool control using Nauticus’ acoustic communication networking technology.

This is wrapped in with wider over the horizon communications – terrestrial and underwater – to support the ability to operate without an umbilical. While satellite communications are there, the rollout of the likes of Starlink will provide more inexpensive ways to transmit more data to the surface, says Radford. For through-water communications, Nauticus has been working with Schlumberger, from whom Nauticus has licensed use of an underwater modem previously tested from a DriX USV to receive video from an AUV. It’s also been work with Singapore-based Subnero.

Subnero has been developing software defined underwater acoustic modems for communications, networking, navigation and monitoring, which it calls Wireless Networked Communications (WNC). Recent testing with Nauticus has included the ability of their WNC to dynamically adapt to provide the best performance in a given environment.

Concurrently, Nauticus is building, through Diverse Marine in Cowes, UK, an 18 m, aluminum-hulled, SMART-Gyro (from Golden Arrow) stabilized USVs called Hydronaut, which will act as a transport, recharge and communication gateway for Aquanaut. Nauticus has an agreement with Diverse to build 20 Hydronauts, with the first two initially scheduled for completion in Q1 and Q2 2023. The rest are expected to include Jones Act compliant builds via Diverse Marine’s USA-based shipyard partners.

Artist rendering of the Hydronaut. Image courtesy Nauticus

Artist rendering of the Hydronaut. Image courtesy Nauticus Hydronaut under construction. Image courtesy Nauticus

Hydronaut under construction. Image courtesy Nauticus

The Hydronauts will have a Guardian Autonomy package from Marine AI, in Plymouth, UK, a launch and recovery system from Kongsberg and through-hull deployment for transducers and other acoustic communications systems. It will be initially flagged to MCA Workboat Code and optionally uncrewed, because “we don't want to be limited by any regulations,” says Radford (an approach others are also taking with many countries having different regulations), “so it has accommodation for four crew. That will allow it to travel about 160 nautical miles from a safe harbor with its crew.”

The firm is also commercializing the manipulator it designed for Aquanaut as a standalone product to sell. “Building Aquanaut was like a moon shot engineering activity and there was a bunch of spin out technologies that are finding their own independent revenue streams, whether it's the software stack called Toolkit that runs everything or all the way down to just the manipulator,” says Radford. “There weren’t really any electric manipulators in the market, so we decided to fill that gap made our first delivery to IKM (in Norway).” That’s been through some development work with IKM and now the first production batch has now started, he says.

Earlier this year the firm also agreed to work with Stinger AS, a specialist underwater technology firm, also in Norway. The details of that are being worked on, says Radford. Nauticus also had an agreement with Triumph Subsea, a new company that had announced various plans for a new breed of greener offshore vessels. There is still a contract with them, but delivery dates have been pushed out, he says Radford.

While there have been delays – building the Hydronauts has been hit by delays getting hold of aluminum – Radford is fired up. “We are here to make the biggest impact in the ocean economy through the deployment of this robotic navy,” he says. “Now we’ve also transitioned to a public facing entity, we’re on the NASDAQ and everyone here is fired up about it.”

He also hopes that Nauticus’ investment will be part of a wider surge in investment in the ocean space, which spending has been dwarfed by other sectors, not least space technology. There are also barriers to entry – the cost to develop ocean technology, for example. But Radford hopes to overcome that, finding both funding and willing partners.