Top down or bottom up, new technologies are helping the industry boost their leak detection and repair (LDAR) strategies

As the world approaches 1.5°C, the presumed threshold of dangerous warming, action to reduce methane releases is seen to be a way of buying time for achieving longer term CO2 cuts.

However, as ABS points out in its recent Sustainability Insights paper, current emissions estimates may be under-reporting the truth. Princeton University and Colorado State University researchers concluded that five times more methane is being leaked than reported from oil and gas producing platforms in the UK North Sea.

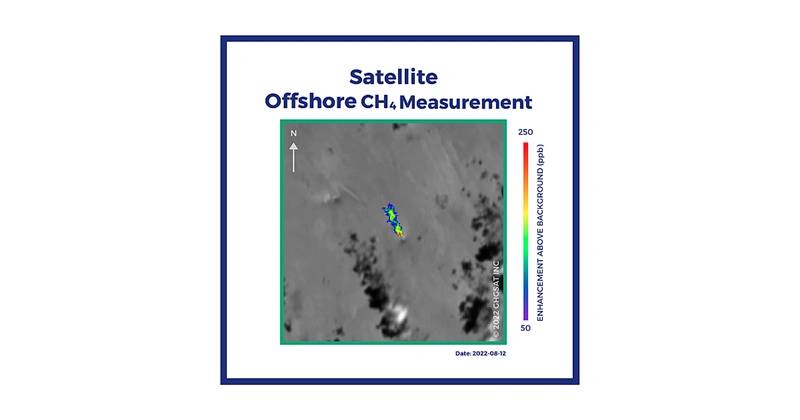

Estimates of methane emissions based on satellite data are already known to be imprecise offshore where reflections from the surrounding water can impact the readings, but that is changing. In 2022, Chevron partnered in a pilot to test GHGSat satellite technology developed for offshore environments. Subsequently, GHGSat detected what was the smallest offshore methane emission ever seen from space. It was observed at an oil and gas platform in the Gulf of Mexico and measured at approximately 1,500 kg/hr. Chevron partnered in a pilot to test GHGSat satellite technology developed for offshore environments. Source: GHGSat.

Chevron partnered in a pilot to test GHGSat satellite technology developed for offshore environments. Source: GHGSat.

According to Oil and Gas Climate Initiative (OGCI) 2021 performance data, venting and fugitive leaks account for over 60% of aggregate upstream methane emissions. Therefore, LDAR continues to be an industry priority, and new technologies are improving leak detection and quantification.

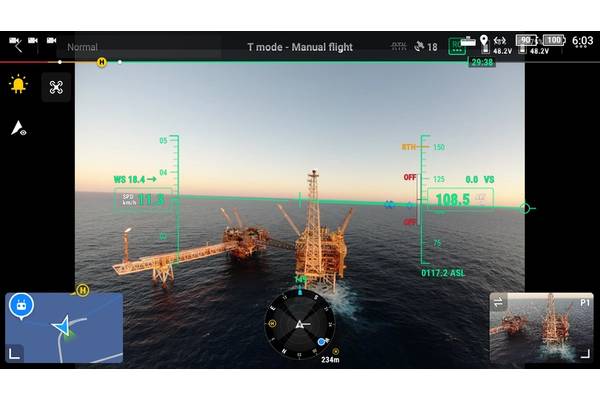

Texas-based Seekops has developed a miniature methane spectrometer which is mounted on drones for offshore methane detection analysis. Based on NASA technology used on the Mars Curiosity rover, it can detect methane concentrations down to 10 parts per billion, pinpoint sources and quantify emissions as low as 20g/hr using wind data in its algorithms. Testing has demonstrated accurate quantification of emissions offshore to less than 10% uncertainty.

The drones operate around 20 meters downwind from a facility, pinpointing particular sources, such as gas turbine exhaust streams, on different levels within the platform. A bit further out, several hundred meters from a flare, the Seekops technology is still sensitive enough for accurate measurement of unburnt methane.

Business is heating up.

The US and EU are looking to make emitters pay, but customer and corporate goals are becoming important too, even in places where the regulations are not as developed. “It’s early days in many places for measuring and reporting emissions. A lot of operators are still figuring out their strategy,” says Dave Turner, Business Development Director – Asia Pacific for SeekOps. “Here in Southeast Asia, where there’s hundreds of platforms, you can inspect a lot of them very quickly using a drone.”

As detection technology grows in sophistication, a top-down approach is supplementing the more traditional bottom-up approach to LDAR. The aim, says Turner, is to validate bottom-up measurements using a directly measured independent method. Companies are looking to quantify methane emissions at a macro level to reconcile the numbers obtained by identifying specific leaks with drone-mounted or fixed sensors and hand-held tools.

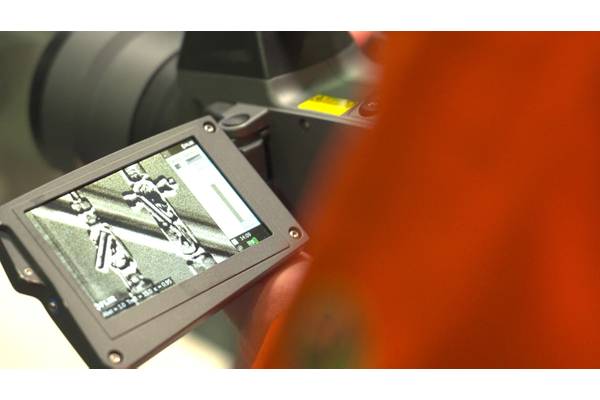

Environmental service providers, such as Texas-based Encino Environmental Services, offer a range of services for detection, quantification, and mitigation, and hand-held equipment is becoming more compact, facilitating rapid on-site assessments. The intrinsically safe optical gas imaging camera Mileva 33 OGI, for example, weighs less than 1.5kg without batteries while still being able to detect methane leaks of less than 0.35g/hr.

Wintershall Dea used two specialist contractors (TP Europe and The Sniffers) in its 2022 LDAR campaign along with various measuring tools - Optical Gas Imaging with an infrared camera can cover 2,000-5,000 sources a day, while sniffing can cover 700-800 sources a day. An ultrasonic internal valve leak device was used to check vent and safety valves, and a bagging technique provided accurate quantification. Drones and airplanes were used to measure emission sources that were difficult to access. In Germany alone, Wintershall Dea found around 249,000 potential leak sources.

These were either immediately repaired or tagged and repaired shortly after, and the company’s methane intensity in 2022 was 0.08%, already below its target of 0.1%.

In 2022, Woodside commenced development of source level, bottom-up methane inventories for its assets and then used top-down methods to assess their accuracy and completeness. Drone-based facility measurements were conducted at several of Woodside’s offshore assets in Australia and the Gulf of Mexico. The program included a trial of the Providence Photonics’s video imaging spectro-radiometry technology for flare monitoring, Mantis Lite. Abatement measures included retrofitting dry seals on compressors and minimizing use of high emitting compressors. In Germany alone, Wintershall Dea found around 249,000 potential leak sources.

In Germany alone, Wintershall Dea found around 249,000 potential leak sources.

Source: Wintershall Dea.

A recent DNV study highlights that key strategies for reducing methane emissions include minimizing venting from processes, improving leakage management and applying optimized maintenance procedures. Across the industry, solutions have also included moving away from pneumatic actuators that use process gas to electric components and the inclusion of fugitive gas recovery systems that send the gas to the flare. Meanwhile OEMs are reducing methane slip from their power and pump systems.

Leaky valves and improperly made fitting connections are primary culprits for uncontrolled fugitive emissions of gases on offshore platforms, says Michael Aughenbaugh, Associate Market Manager, Swagelok. Fugitive emissions from dynamic and static seals on valves, pumps, and flange connections can be mitigated using low emission (Low-E) valves, he says. Manufacturers should guarantee that the valves will not leak above 100ppm for five years or the valves should be tested to ensure leak rates are no greater than 100ppm. “It’s best to capture certain details about those leaks for auditing purposes, as well, so you can identify areas for improvement,” says Aughenbaugh. “A leak that comes back frequently may indicate the need to redesign the fluid system or add supports to reduce vibration.”

Beyond LDAR campaigns, longer-term strategies are being put in place. Wintershall Dea uses an internal carbon pricing metric when making investment decisions and is committed to offsetting its residual upstream GHG emissions by 2030. Woodside has invested in String Bio, a developer of a patented process that converts methane into a protein suitable for animal and human nutrition. So, as well as the value of recovered gas, there is the potential for new revenue streams to add value to abatement strategies.

In Germany alone, Wintershall Dea found around 249,000 potential leak sources.

In Germany alone, Wintershall Dea found around 249,000 potential leak sources.

Source: Wintershall Dea.