The U.S. offshore wind market presents a $1 billion long-term opportunity to builders of crew transfer vessels (CTV) and service operation vessels (SOV) that will support both wind farm construction and long-term operations and maintenance. Unlike many of the construction vessels to be deployed on U.S. wind projects, CTVs and SOVs must be Jones Act compliant, meaning they will be built, owned and operated by U.S. companies and personnel.

However, although seen as somewhat commoditized vessels, a clear understanding of the commercial technical drivers in each of the segments is required.

These are the findings of a new analysis of the global CTV market produced by Intelatus Global Partners.

The CTV and SOV opportunity

By the end of 2024, the U.S. Tier 1 (purpose built) and Tier 2 CTV (conversions) fleet will have grown to 23 vessels, with owners holding options to build at least a further 12 vessels.

Long-term, the market has a potential O&M related demand for 60-130 CTVs with additional CTVs required for logistics during the offshore construction of wind farms. MARAD Title XI loan guarantee documentation indicates U.S. CTV pricing of around $12 million per vessel. As a result, the net long-term capital requirement for new CTV construction is $440-1,140 million. Construction cycle time is at least 12 months per vessel (and as much as 15-20 months) excluding design and approvals. Most yards involved in the building of CTVs for the U.S. market appear to be able to produce between one and four CTVs annually.

By comparison, leading Southeast Asian yards will sell European specification CTVs for around $5.5-6 million per vessel, with build cycles of 8-10 months and capacity to produce 10 vessels a year.

We note similar pricing trends in the SOV segment as seen in the CTV segment. We have reported previously the price difference in U.S. built SOVs compared to those deployed in Europe and the three Tier 1 vessels currently being built in the U.S. are reported to cost between $97 and 162 million each. SOVs contracted for the European market at a similar time to the three Jones Act vessels cost between $67-75 million.

Where the right conditions exist, such as a developer or turbine OEM operating a large number of turbines in a relatively close geographic proximity, Tier 1 SOVs will be used for turbine commissioning and O&M support. Tier 2 walk-to-walk vessels, mainly redeployed from the Gulf of Mexico’s oil & gas sector, will also be used for turbine commissioning and some maintenance work from time to time. Vessels falling into this category include the Paul Candies and one of the Hornbeck HOSSOV 300E MPSVs.

There remains potential for additional Tier 1 vessels, with at least three vessels currently identified by developers, for an estimated CAPEX of $450-500 million.

To confirm the theme of comparatively high costs for locally built vessels, in its Q2-23 financial reporting, Dominion Energy has reported that the construction of the U.S.-built wind turbine installation vessel (WTIV) Charybdis had cost $367 million as of June 30, 2023, and is forecast to rise to around $625 million by time of delivery at the end of 2024 or early 2025. To put this in context, WTIVs contracted in Asian yards with similar specifications in the same time period as Charybdis, cost around $325 million. The delayed delivery means that the vessel will (most likely) not be deployed on Ørsted’s Revolution Wind and Sunrise Wind projects.

Drivers for CTV and SOV demand

Those reading about U.S. offshore wind over the last few months will have experienced roller coaster emotions, lurching between optimism and pessimism.

Developers have reported projects have become unfinanceable due to a combination of inflationary factors, U.S. specific tax credits and supply chain challenges. Several of these developers have sought to renegotiate or cancel contracts to sell electricity to states for agreed rates by agreed dates. As a result, some projects will see completion dates shift back for several months to even years.

However, the fundamental drivers for offshore wind remain sound. At the federal level, the current administration is focusing resource on the leasing and permitting of offshore wind and plans to approve over 13 GW of project capacity before the end of 2024 and provide financing support through the Inflation Reduction Act related tax credits.

At the state level, especially for the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic segment, we see states with clear ambitions to increase the use of renewable energy, reduce the amount of imported hydrocarbons, setting offshore wind procurement targets and creating a clear route to market for developers.

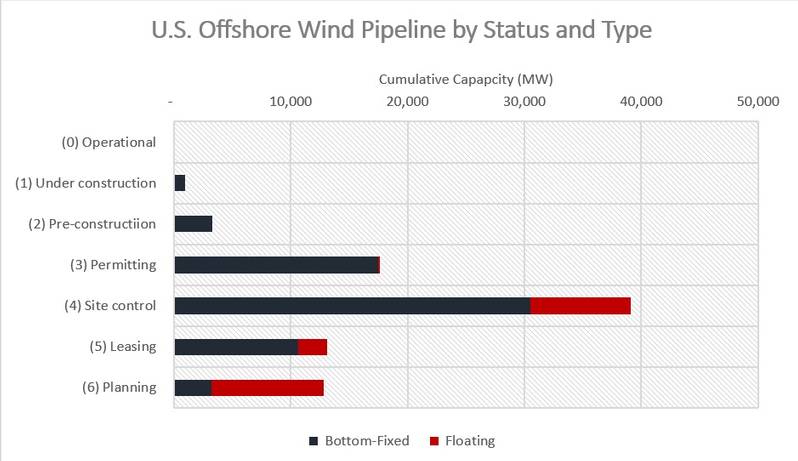

Our 87 GW project pipeline, shown in the chart, covers 73 wind farms located in federal and state waters off the Atlantic. Pacific and Gulf of Mexico Coasts as well as in the Great Lakes. 42 MW of capacity is operational, 938 MW currently in offshore construction and a further 3.3 GW of capacity has passed the final investment decision hurdle.

U.S. OFFSHORE WIND PIPELINE (Source: Intelatus Global Partners)

U.S. OFFSHORE WIND PIPELINE (Source: Intelatus Global Partners)

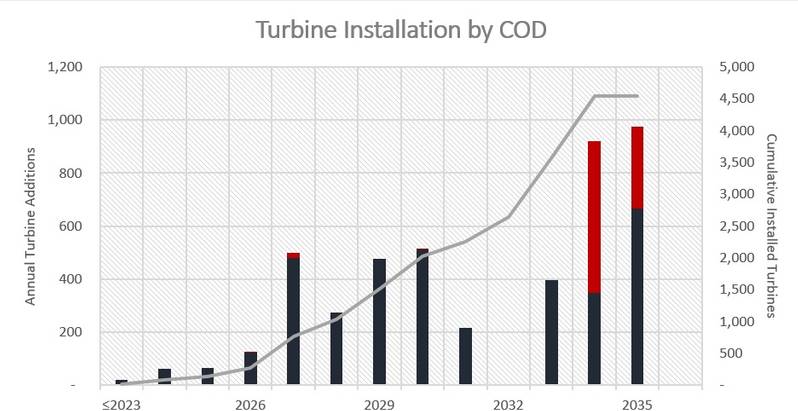

A good barometer for long-term CTV activity is to look at the number of turbines that will be installed as during their long lifetime, they will require constant routine inspection, repair and maintenance, the technicians for which are transported and/or housed on CTVs and SOVs.

Based on current developer plans, the pipeline translates to close to 4,500 turbines being installed in U.S. waters by 2035, which are expected to be supplied by the three dominant western OEMS: Siemens, GE and Vestas.

U.S. TURBINE INSTALLATION FORECAST BY COD (Source: Intelatus Global Partners)

U.S. TURBINE INSTALLATION FORECAST BY COD (Source: Intelatus Global Partners)

Looking to other markets for guidance

The mature and large European offshore wind market can be used as a guideline to developments in the CTV and SOV market space.

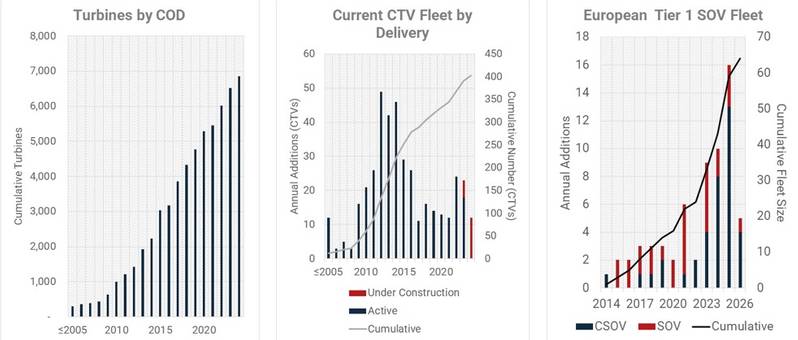

Europe is expected to have installed close to 7,000 turbines in total by the end of 2024. By the end of 2024, slightly more than 400 Tier 1 CTVs will be operational in Europe, supporting both long-term operations and maintenance support for existing wind farms as well as construction and commissioning of new wind farms. At the same time, 43 Tier 1 SOVs are expected to be working for developers and OEMs, a number which will jump to 64 by 2026 (although not all of these are contracted).

EUROPEAN CTV AND SOV MARKET (Source: Intelatus Global Partners)

EUROPEAN CTV AND SOV MARKET (Source: Intelatus Global Partners)

What about Tier 1 technical trends?

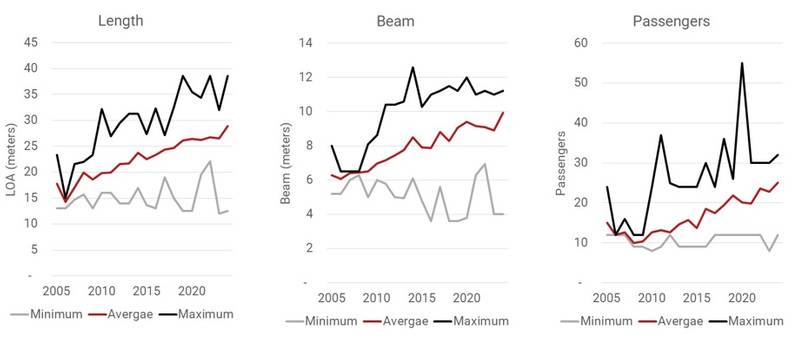

On average, CTVs have become longer, wider and feature increased passenger capacity.

CTV TECHNICAL TRENDS (Source: Intelatus Global Partners)

CTV TECHNICAL TRENDS (Source: Intelatus Global Partners)

Catamarans remain the dominant hull type, but there are also an interesting number of surface effect vessels, SWATH (small waterplane area twin hull), trimarans, CTVs featuring outriggers and a CTV featuring a hydrofoil.

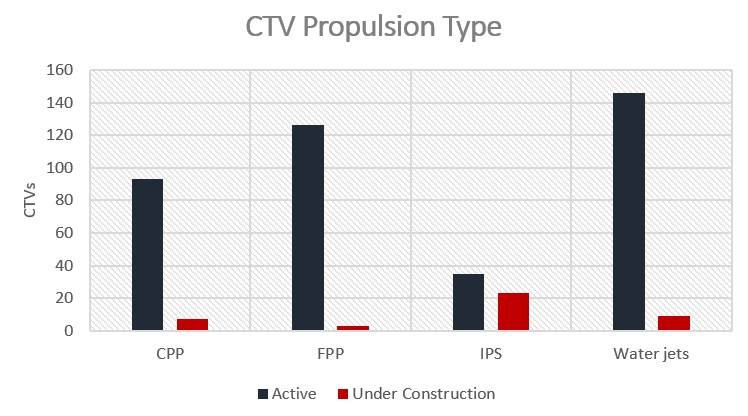

Waterjets and twin fixed pitch propellors are the leading solutions for active vessels, but the Volvo Penta quad IPS system has gained much favor, featuring in over 50% of new builds.

CTV PROPULSION TYPES (Source: Intelatus Global Partners)

CTV PROPULSION TYPES (Source: Intelatus Global Partners)

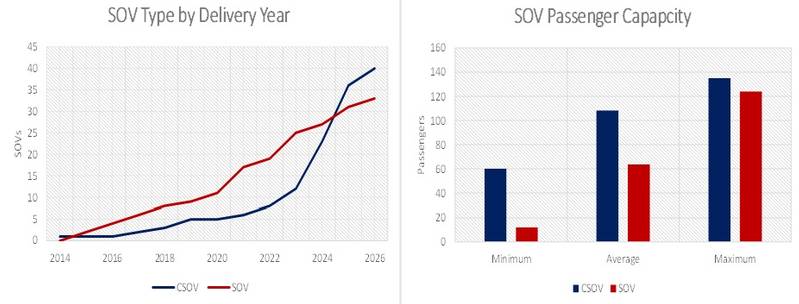

The SOV segment is defined by those vessels more focused towards longer term O&M work and those vessels suited to turbine commissioning projects, the latter which generally requires more technicians to be housed. As the charts show, the long-term contracted SOV supply has grown at a fairly steady rate, whereas the SOV segment is currently going through a significant growth spurt. The one concern for this segment remains that SOVs are a comparatively commoditized item, which is relatively easy to package and explain to investors, fueling the risk for speculative and over-building.

SOV TECHNICAL TRENDS (Source: Intelatus Global Partners)

SOV TECHNICAL TRENDS (Source: Intelatus Global Partners)

The trend for the SOV segment is for battery-based diesel electric propulsion systems, where the engines feature some form of fuel flexibility to accommodate hydrogen energy carriers, such as methanol and liquid organic hydrogen carriers (LOHC).

Still a bright future

Offshore wind projects, whether in the U.S. or globally, are navigating some significant obstacles, whether supply chain bottlenecks, financial support or inflationary pressures. However, the fundamentals remain strong for growth of offshore wind projects in Europe, East Asia and the U.S. Further, we anticipate new market entrants, including South America and Australia.

A common theme of all of these projects is that they will require logistical support during construction and operations. CTVs and SOVs remain key assets for these activities, and more will be required.

But to avoid the challenges that have been faced by many early movers, lower risk long-term charter contracts with no early termination provisions should always be considered as a potential option.