The stately Norwegian operator’s foray into South Australian offshore and Norway’s remote areas is being contested by increasingly successful green groups.

A first installment of Norwegian operator Equinor’s plans to drill and develop oil reserves in Australia has been delivered to regulators Down Under, and already that first, deepwater exploration well is under attack.

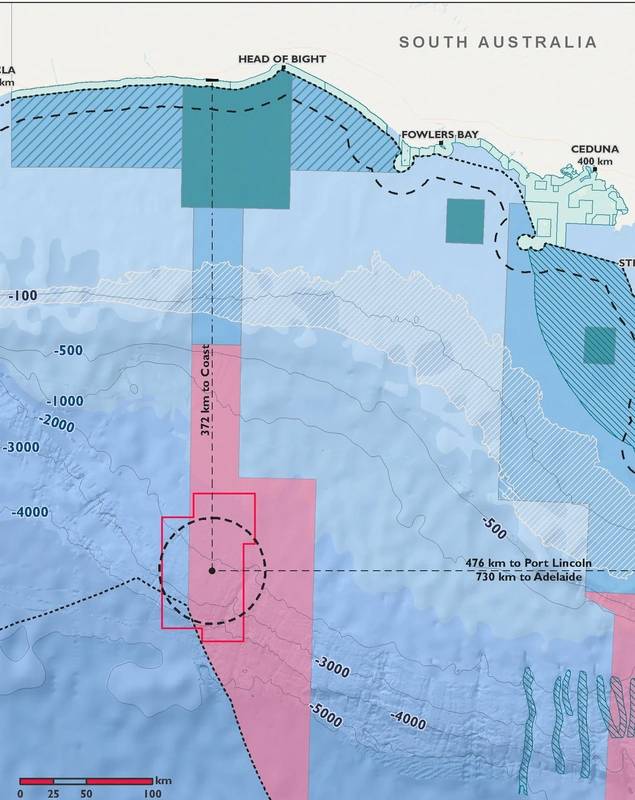

Australian environmentalists on surfboards and in kayaks converged outside of Oslo’s opera house landmark on Sunday to bring attention to the imminent drilling of Equinor’s first well in the remote Ceduna Basin, some 370 kilometers offshore South Australia. The protests this time have merely resulted in a revised Equinor environmental impact assessment for the Stromlo-1 well that’ll go down in 2,400 meters of water.

“We’re asking Equinor to pull out,” a protesting environmentalist surfer was quoted by Norwegian NRK as saying. The surfers dove into Oslo Fjord with their Norwegian allies hoping to keep drill bits from license EPP 39 — a frontier area of 99 blocks which Equinor’s exploration manager for Australia, Camilla Aamodt, says is “similar to Norway”.

The surfer involvement coincides with an increased tempo of protest against offshore energy, some of it seemingly successful, The Norwegian arm of Greenpeace recently boarded an arctic-bound rig, made headlines, and then disembarked without incident, after a long period of inactivity.

In recent months, some of the larger political objectives of environmentalists in Norway have been reached, and the result suggests the potential for future limits on activity in pristine areas. A recent parliamentary control commission seemed to side with the greens, when it said the vaunted Petroleum Safety Authority — which became a model for US offshore regulators post-Maccondo — was not acting in time and not acting enough, after a run of incidents, accidents, breached routines and “ghost-in-the-machine” leaks (to quote a UK HSE executive).

Greens celebrated, too, when Norway’s ruling, right-leaning coalition government said it would sell off ownership shares in worldwide, but not Norwegian, upstream oil companies. The finance ministry said it was protecting the Norwegian economy from oil-price volatility, but it was seen as “victory” by greens (and the public).

Equinor target: the Cedun Basin, South Australia (Image: NOPSEMA)

Equinor target: the Cedun Basin, South Australia (Image: NOPSEMA)

Green victories

While Equinor waits out 2019 to learn whether Australian regulator, NOPSEMA, will okay its 1,500-page environmental impact assessment (EIA), Norwegian greens are already cheering a decision by the country’s Labor party congress not to make the pursuit of drilling in the protected Lofoten protected area part of its political platform.

To be sure, Equinor — which changed its name from Statoil in part to reflect its green energy investments — has had to renew its 2011 Australian exploration license a pair of times due to inactivity. It might, again, not renew the license by its expiry date in April 2024 if politics or publicity issues delay work start in the 6,295-square-kilometer area.

BP and Exxon have already reportedly dropped their own designs in the license area. There’s no telling if Equinor, with one employee in Australia, will stick around despite spending no fewer than two years on the EIA.

So, for now look for a start to 60 days of drilling between October 2020 and May 2022. There’ll be no drilling in the southern winter due to weather and whales.

A semisub and three platform supply vessels (PSV) are in the works, with supply from Port Adelaide and daily helicopter support from Ceduna. There’ll be no coring and testing of the well, if drilled. It’ll be plugged and abandoned after reservoir analysis.

So, all that — if there’s no pull-out. But, activists are now availed by key facts on the oceans and served, too, by the specter of Macondo in the Gulf of Mexico (GoM). There’s also the success of other activists to encourage them: the French protestors who this week stalled Saudi arms purchases at a French port; and those who have impacted salmon-farming laws off Western Canada and the United States, whatever the veracity of their science.

Equinor says it has “broad political support” in Australia, and the Aussies are trying to build up their local supply chain. The Basin could be one of Australia’s largest untapped oil reserves, and the Norwegians could help.

With their vigorous, barrier-focused regulators and effective union involvement, Equinor has the offshore pedigree. “I’m pleased that all our science and experience tell us that we can do this safely,” Aamodt says.

Previous activity

The waves and weather off South Australia are said to be “similar to the Norwegian Sea”, a gas province. The goal, this time, is oil however.

To counter seabed damage, rigs will use DP only, rather than anchor-drops, along with satellite, wind, transponders, gyroscopic controls and heave compensation. Unlike Macondo, a 400-metric-ton blowout preventer (BOP) will have six shear rams attached to pinch off trouble, and they’ll be controlled via remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROV) and aboard-rig.

So far, the proposed new oil region has seen two dozen wells drilled, including 13 in the Bight. There’s been no harm to the environment reported.

Against those concerns, Equinor — which has spent $14 million on Aussie exploration and general expenses, has yet to earn a penny in Australia. But Bight contains one of the last great, underexplored basins and therefore the potential for nation-building.

That’s the reward for the risk felt by the Aussie surfers in Oslo.

Equinor spending in people, property, technology, offshore assets and royalties are the reward. This week alone, to offer a token of scale, Equinor said it will spend nearly $1 billion for a quarter of Shell’s Caesar Tonga oilfield in the GoM.

For those involved, Equinor in South Australia feels like high-risk, high-reward. Let’s ensure that any, eventual greenlight on Stromlo is of benefit to all and everything.

(Photo: Jani Sipilä / Greenpeace)

(Photo: Jani Sipilä / Greenpeace)