The decommissioning market is making a comeback, with new fields of opportunity, and challenges, opening. TSB Offshore President Will Speck shares insights on the path ahead.

With the decommissioning market slowly recovering, TSB Offshore is looking to 2020 to be a year of growth and expansion for both the market and the company.

The decommissioning market is growing, but it’s difficult for a number of reasons. Chief among those reasons is the fact that there is no revenue to the operator associated with removing aged equipment from an offshore field combined with decommissioning’s role as the largest liability on an operator’s balance sheet. Further complicating the issue is that inadequate details about an asset or well can lead to surprises during the decommissioning process, and those surprises usually increase the project’s cost. Yet a third is evolving market needs, thanks partly to a variety of regulations in place in other parts of the world and partly to the industry’s march into ever deeper water, which results in different types of infrastructure that must be decommissioned.

TSB Offshore, with headquarters in The Woodlands, Texas, sees these challenges as growth opportunities, and the company’s new president, Will Speck, is enthusiastic about the potential to increase the company’s operations around the world.

“Things are recovering slowly,” says Speck, who’s been with TSB Offshore for seven years. “The last couple of years we had a fairly steady market.”

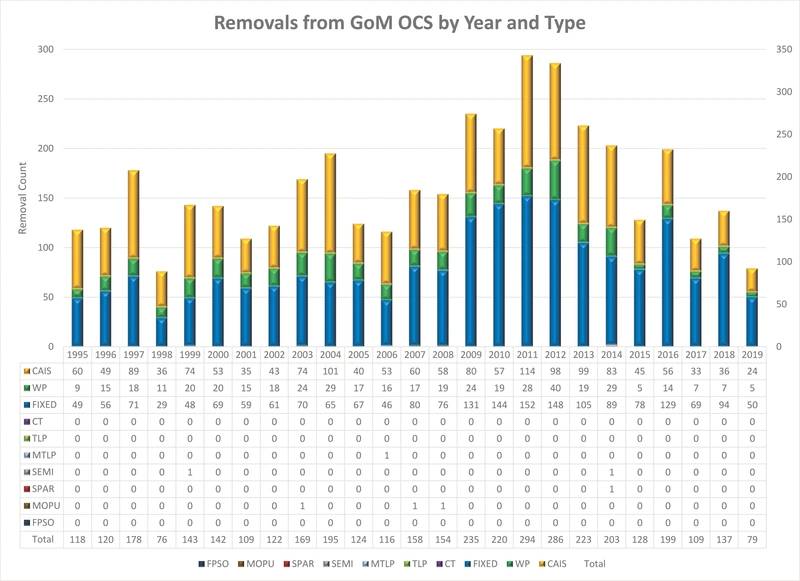

According to the US Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE), 137 structures were removed from the Gulf of Mexico Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) in 2018, while 79 were removed in 2019. Due to the aging of infrastructure in increasingly deeper waters, Speck expects deepwater decommissioning activity, along with related deepwater reefing, to rise in the coming years.

That will create a potential learning curve as the industry works out the best way to remove aged tension leg platforms (TLPs), compliant towers, and spars. Additionally, updated decommissioning regulations addressing the challenges of deepwater decommissioning activities will be required.

“Those are starting to be lined up for decommissioning, and we’ve only seen a handful removed so far,” Speck says. “We will see innovations, new methodologies and technologies (for decommissioning) that we hope will drive costs down.”

In a typical decommissioning scenario for a fixed platform, the topsides are removed to shore for re-use or recycling, while the substructure is severed 15 feet below the mudline and taken to shore for recycling or refurbishment. In some cases, however, an operator can apply for part of the substructure to remain as an artificial reef through the National Artificial Reef Plan. Good candidate platforms are those that are complex, stable, durable and clean, according to BSEE, while those that have toppled due to structure failure are not.

“Deepwater reefing is coming into vogue,” Speck adds, noting that leaving more of the structure behind during decommissioning activities creates more biohabitat that allows a larger variety of marine life to grow in the area.

(Source: Generated by TSB Offshore based on BSEE data)

(Source: Generated by TSB Offshore based on BSEE data)

Increasing demand

Decommissioning activities are also expected to increase along the US West Coast where that infrastructure is reaching the end of its service life. What complicates that market, Speck observes, is the difficulty in mobilizing vessels to the region to carry out the activity. Any vessel will likely come from Asia or the Gulf of Mexico via the Panama Canal. As a result, he says, it is possible multiple Pacific OCS operators might cooperate in sharing vessel assets to reduce the overall mobilization burden.

Elsewhere in the world, Malaysia is starting decommissioning activities and Thailand’s decommissioning pace is picking up, he says. The level of activity offshore both Australia and Brazil are likely to be similar, he adds, although each has its own challenges. For instance, Australia’s geography imposes logistics challenges almost akin to the US’s West Coast, he says, because vessels often have to mobilize from the other side of the island or from Singapore. Brazil, on the other hand, is continuing to develop its decommissioning regulations, he says.

“As they streamline their processes, Brazil will be a market to watch,” Speck says.

West Africa is another region where regulations are firming up, he adds.

“This is going to push the decommissioning planning, which is important,” he says. He says some West African countries like Equatorial Guinea, Angola, Ghana and Gabon are starting to look at decommissioning from the outset of a new field’s development. “That’s an excellent improvement.”

And a new decommissioning market is also opening up: offshore wind farms.

With the first generation of windfarms starting to age out, Jay Boudoin, TSB Offshore’s director of client relations, believes the company will have to opportunity to participate in those decommissioning efforts as well.

Liabilities and challenges

While it is necessary to decommission assets once they’ve reached the end of their useful life, Speck says, operators don’t want to spend any more on the operation than necessary.

“Decommissioning is a zero-profit effort,” Speck says. “The more money you spend, the more money you spend. You’re not getting anything in return.”

As Boudoin puts it, decommissioning is the operator’s largest liability on the balance sheet.

“Having an accurate snapshot of that is very important” for the operators as well as their auditors, certified public attorneys and equity investors, Boudoin says.

One client wanted a full understanding of their decommissioning liabilities in the Gulf of Mexico, where there were more than 20 platforms, 60 pipelines and 200 wells.

“We reduced their total liability estimate by more than $150 million,” Speck says.

One of TSB Offshore’s roles is to help operators determine how much and when to spend on decommissioning and help potential asset buyers understand the decommissioning liabilities they may be taking on with the purchase.

But sometimes even after an asset is sold, decommissioning liabilities can “boomerang” back to a previous owner, Speck says. This can happen if an asset owner folds, in which case BSEE will work its way up the chain of title seeking a previous owner to take responsibility for a liability thought to be shed years before.

Speck cites a recent case where a pipeline was abandoned in place in the 1990s, but the area was recently identified as having desirable sediment resources. As a result, BSEE notified the former owner the pipeline must now be removed entirely.

The base of the High Island 389A structure is an artificial reef within the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary. (Photo: G.P. Schmahl, the NOAA Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary)

The base of the High Island 389A structure is an artificial reef within the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary. (Photo: G.P. Schmahl, the NOAA Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary)

The power of good data

“With decommissioning, there are a large number of unknowns,” Speck says.

One of the best ways to minimize costs for decommissioning is minimize those unknowns by maintaining quality data about the assets. Over the years, he says, he’s worked on projects where files have been inattentively kept or worse, misplaced or damaged in floods.

“The quality of the information will directly impact the efficiency of the operation,” Speck says.

TSB Offshore relies on its Platform Abandonment Estimating System (PAES) software to perform fast, repeatable and detailed decommissioning cost estimates. PAES was developed more than 30 years ago so it has gone through many iterations and updates as the industry innovated into ever deeper waters. PAES helps with concept selection and assessing multiple removal scenarios.

“We have about 30 years of data and various methodologies,” Boudoin says.

Being able to plan contingencies makes it possible to minimize cost escalations.

“Surprises are when the costs explode,” Speck says.

He recalls one project where executing an abrasive cut on a piling took three times longer than expected because the wall thickness was much greater than records indicated.

“It was like the difference between a hollow Easter bunny and a solid one,” Boudoin says.

Speck believes abrasive cutting will continue to expand as a choice technology instead of explosives. Diamond wire is becoming more efficient with smaller profiles, and it can be run via remotely operated vehicle (ROV) to remove portions of a structure.

On the cementing side, he says, resins are gaining acceptance for well plug and abandonments. In places where cement is setting, any slow gas bubbles will channel through that cement, which means there is no real barrier for pressure containment. But, he says, by topping the cement with resin, even if gas bubbles through the cement, the resin encapsulates the gas. The resin gives the cement time to cure.

“Resins can be a great option, especially for downers or bubblers.”

Downers are structures or wells that were damaged due to age, impact or storm effects. Bubblers are abandoned wells that develop a containment leak, allowing gas to bubble from the abandoned well.

"Deepwater reefing is coming into vogue." - Will Speck, TSB Offshore President (Photo: Jennifer Pallanich)

"Deepwater reefing is coming into vogue." - Will Speck, TSB Offshore President (Photo: Jennifer Pallanich)

Time for growth

Speck, who holds a mechanical engineering degree and is a licensed professional engineer, has worked in field operations, project management and operations management with Schlumberger, GE Wellstream and TSB Offshore. He was previously TSB Offshore’s director of operations.

“We’re looking to expand our services, especially overseas,” Speck says. In 2019, about a third of the company’s work was overseas.

One of the areas of growth that excites Speck is the ability to assist countries and regulatory bodies codify regulations and processes. The company conducts decommissioning workshops around the world, and aims to grow its land-based decommissioning activities for LNG facilities, production facilities, land assets and fields.

“We’re focusing on being lean and efficient,” Speck says.